by Jessica Santascoy

What is it that makes the Alexander Technique unique? One of the main ideas is primary control, and the understanding that it can help balance the whole body.

What is Primary Control?

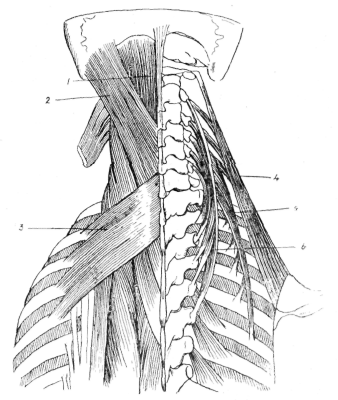

Primary control refers to how the head, neck, and torso are working together. When primary control is working well, the head is poised at the top of the spine, and the neck muscles are supple and flexible. When primary control is not working well or has vanished, more muscles are recruited than are needed for movement, there is more joint compression, and there is stiffening. The head becomes a weight. The whole body will eventually feel the impact of the loss of primary control.

If the head, neck and torso are working efficiently together, then we have more ease, which equals higher productivity and more energy, because the body is freer.

Effortless Learning

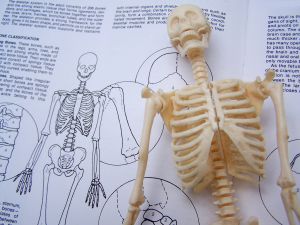

Muscle System Pro III is an excellent anatomy app that can help you understand or explain primary control and other dynamics of the body.

One of my favorite features of the app is the robust amount of 3D animations. They help demonstrate key principles and can lead to “a ha” moments. Let’s take a peek inside Muscle Pro III, and find out how it can help you explain or learn about primary control.

Laptop Pain

A friend of mine had tremendous neck and back pain. She was working in cafes, where the screen of her laptop was about 4 inches lower than her eyes. She was dropping her head towards the laptop to see the screen. Her head became a weight, pulling on her neck and back. After working this way for 6 hours or so, she was in excruciating pain, very irritable, often had a headache, and had to stop working. (See Figure 1.)

Ease Pain with Primary Control

Through Alexander lessons, my friend became aware that allowing her head to drop down was causing a lot of the pain. The laptop had become a stimulus for her to “dump” her head - when she’d start working on the laptop, she dropped her head down. She realized that she could choose not to do this, and learned a better way to work, using only the muscles necessary and moving the head at the top of the spine (at the atlanto-occipital joint). (See Figure 2.)

Now, my friend uses less muscular action and effort, and gets more done because she’s not in pain. She is proactively preventing pain, which increases productivity.

What Do You Think About Learning Anatomy?

In my experience, learning anatomy clarifies learning and helps bring about a deeper understanding of Alexander principles.

What do you think? Does understanding anatomy help you learn? Teachers: What are the advantages of using anatomy to demonstrate primary control and other principles? Are there disadvantages to teaching with anatomy?

Features in the App Include:

A robust amount of media, including animations showing movement of the body including articulated area and range of motion; still images with different views: anterior, lateral, posterior

3D perspective and ability to move the images

Remove and add layers of muscles quickly

Quick access to information - including audio pronunciation, origin, insertion, action, and nerve supply of a muscle

The ability to take notes in the app, and share images via social media

For Teachers

I recommend getting these apps by 3D4Medical for your app library: Muscle System Pro III, Skeletal System Pro, and the free Essential Skeleton 3. You can switch between the apps to show your student various views and media to clarify concepts. There are iPhone, iPad, and Mac versions. No Android version at this time.

For Learners

My friend bought Muscle System Pro III for iPhone, so she could have a quick review of what she’d learned at the lesson. The iPhone version is an inexpensive investment for your learning, at $3.99.

App images via Muscle System Pro III by 3D4Medical

Top image: Joe Cieplinski

JESSICA SANTASCOY is an Alexander Technique teacher specializing in the change of inefficient habitual thought and movement patterns to lessen pain, stress, anxiety, and stage fright. She effectively employs a calm and gentle approach, understanding how fear and pain short circuit the body and productivity. Her clients include high level executives, software engineers, designers, and actors. Jessica graduated from the American Center for the Alexander Technique, holds a BA in Psychology, and an MA in Media Studies. She teaches in Boulder. Connect with Jessica via email or on Twitter @jessicasuzette.

Experiential Anatomy and Alexander Techniquewith Witold Fitz-Simon

Experiential Anatomy and Alexander Techniquewith Witold Fitz-Simon by Witold Fitz-Simon

I’ve been noticing over the past few weeks how a few of my Facebook friends have signed up to be part of an event for the month of June: "30 Day Ab Challenge for those who need some motivation like me.” I clicked over to the event page and was surprised that 1.9 MILLION Facebook users have said they are going to take part. I work both as an Alexander Technique teacher and a Yoga teacher, so I spend a certain amount of my working week in gyms. I understand the pressure to look trim and have a slim waist, and I see the effort people put in to the goal of hard abs. I also see the harmful effects this can have on them. Tight abs can be really bad for the body, and here are five reasons why:

by Witold Fitz-Simon

I’ve been noticing over the past few weeks how a few of my Facebook friends have signed up to be part of an event for the month of June: "30 Day Ab Challenge for those who need some motivation like me.” I clicked over to the event page and was surprised that 1.9 MILLION Facebook users have said they are going to take part. I work both as an Alexander Technique teacher and a Yoga teacher, so I spend a certain amount of my working week in gyms. I understand the pressure to look trim and have a slim waist, and I see the effort people put in to the goal of hard abs. I also see the harmful effects this can have on them. Tight abs can be really bad for the body, and here are five reasons why:

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The standard wisdom is that it is only the muscles of the human body that contact and create movement, but it turns out that this is not entirely true. About ten years ago, research began to show that fascia contained

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The standard wisdom is that it is only the muscles of the human body that contact and create movement, but it turns out that this is not entirely true. About ten years ago, research began to show that fascia contained