by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

For a lot of people, sexual intimacy is an attempt to return to our bodies and feel whole. We spend so much time in our heads, experiencing life not fully in our bodies, not feeling the integration of our system. There is so much fixation on finding a partner and experiencing intimacy as a way to feel connected and validated. Through Alexander Technique we practice feeling whole so that we don’t need to be in our front bodies grasping for more. We can be aware of our back bodies, our head moving forward and up, neck free, torso widening and deepening, knees moving forward and away. All of the parts create a simultaneous awareness of the whole: one at a time and all together.

A lot of the pain I experience in life comes from a feeling of being disconnected and isolated. There’s a quote I love by Lawrence LeShan, “It is the splits within the self that make for the feeling of being cut off from the rest of existence.” I am slowly learning how to experience myself without all the splits -- to gather all my different sides --shawdowed and bright -- and hold them into a unified whole.

This past winter I was severely depressed and felt as if my Self were fragmented into tiny meaningless pieces. I felt alone in my head, and disconnected from myself, loved ones, or any purposeful connection. My mind was full of vicious and self-loathing thoughts, and I tried to escape the abuse by fleeing from my body and myself and towards someone I was romantically interested in. I have learned, again and again though, that true resolution comes from staying -- creating space for the pain, witnessing it, holding it, and integrating it into my whole self. If I try to reach outside of myself to escape pain, that only takes me further from home.

I recently took a course on Visceral Manipulation, taught by Liz Gaggini. We learned that in order to heal a client’s organ, you must have an attitude of nonchalance and only put some of your attention on the person. The rest of your attention will stay in your body, in the room around you, and beyond. In order to heal another, you must stay whole. If you give too much, you offer the person a fragmented presence, an energy that is coming just from the front of the body -- a grasping, an end-gaining.

This is so true for relationships. When connecting with another person, even someone to whom I’m greatly attracted, I can practice not coming forward into the pull of hormones and craving, but remain in my full body. There is much pleasure to feel just here as I am, inside myself. This is a new and exciting practice, to realize that simply walking around and being inside my body can feel good, especially after the last 5 years of chronic pain and health problems. I am learning how to hold pain as part of the experience, not the only thing. I am learning to accept all the parts of myself, and to hold them in an awareness that is deep and fulfilling.

This past winter I liked someone so much that I lost my awareness of my back body. I fell forward. I fell hard.

And the ironic thing is, I was leaning forward in order to feel a connection -- to return home. But home is back and up into my torso, widening and deepening, my head moving forward and up, my gaze softening, my neck being free.

Here I am again, having remembered, but life is a process of forgetting and remembering, of getting lost in the pieces, and then expanding our awareness to perceive more. Alexander Technique is the gentle practice each day to return to our whole.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/helsinki-sun-headshot.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]MARIEL BERGER is a composer, pianist, singer, teacher, writer, and activist living in Brooklyn, NY. She currently writes for Tom Tom Magazine which features women drummers, and her personal essays have been featured on the Body Is Not An Apology website. Mariel curates a monthly concert series promoting women, queer, trans, and gender-non-conforming musicians and artists. She gets her biggest inspiration from her young music students who teach her how to be gentle, patient, joyful, and curious. You can hear her music and read her writing at: marielberger.com[/author_info] [/author]

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Yoga teachers giving adjustments has become a

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Yoga teachers giving adjustments has become a  by Dan Cayer

I’m not against correcting our posture or body on principle. I wish all it took to rid ourselves of chronic pain and tension was figuring the right angle or position, and tapping our body into place. It’s such a seductive offer; that we need only arrange our body and then get on with the rest of our day.

by Dan Cayer

I’m not against correcting our posture or body on principle. I wish all it took to rid ourselves of chronic pain and tension was figuring the right angle or position, and tapping our body into place. It’s such a seductive offer; that we need only arrange our body and then get on with the rest of our day. by Barbara Curialle

Having spent Thanksgiving week coping with a case of bronchitis, I’ve come away with a few suggestions on dealing with the most irritating (in every sense) part of the problem—the coughing.

by Barbara Curialle

Having spent Thanksgiving week coping with a case of bronchitis, I’ve come away with a few suggestions on dealing with the most irritating (in every sense) part of the problem—the coughing. by John Austin

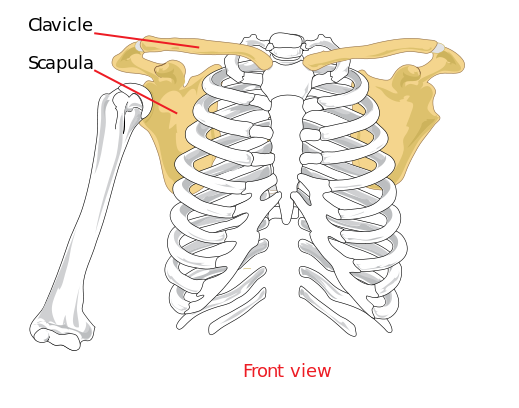

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

by John Austin

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder. by Brooke Lieb

This summer, I decided to check some items off my bucket list while I am healthy, happy and had time. I spent Tuesday afternoons in "Acting for the Camera" in the afternoons, and in a Stand Up Comedy class in the evenings. Although I have a Bachelor's Degree in Musical Theater Performance, I haven't worked on a text or studied acting technique in over 25 years. I have never done Stand Up. The first point at which my AT skills kicked in was the act of registering. I tend to think inhibition is about overtly stopping from impulsive and habitual behavior. In this case, inhibition helped me override the habit of keeping in my comfort zone, to do something new, different and unknown.

by Brooke Lieb

This summer, I decided to check some items off my bucket list while I am healthy, happy and had time. I spent Tuesday afternoons in "Acting for the Camera" in the afternoons, and in a Stand Up Comedy class in the evenings. Although I have a Bachelor's Degree in Musical Theater Performance, I haven't worked on a text or studied acting technique in over 25 years. I have never done Stand Up. The first point at which my AT skills kicked in was the act of registering. I tend to think inhibition is about overtly stopping from impulsive and habitual behavior. In this case, inhibition helped me override the habit of keeping in my comfort zone, to do something new, different and unknown.