Writing with a soft gaze and a loose grip around the pen might mean that you make more of a mess. And the thoughts that make their way to paper might be more of a wandering than an answer. A spiral of questions. Some what-ifs, whys and maybes.

Read moreAlexander Technique at Political Demonstrations

I’m not advising you on who or what to protest, but I marched on Sunday at a big anti-Trump rally in Midtown Manhattan. As I was remembering my Alexander principles, I came up with a few guidelines for participating in the demonstration or march of your choice.

Read moreElection Cycle Fatigue: What you can do to take care of yourself and those around you

by Brooke Lieb The first time I voted in a Presidential election was 1984. My memory is far from perfect, but I cannot recall a presidential race that began as early as the 2016 race, with one party's campaigning for the nomination starting in March, 2015; nor can I remember the type of rhetoric I am hearing as overt and extreme in US politics as it is during this election.

Frankly, it frightens me. And I am not alone. There are a plethora of articles about the heightened anxiety levels precipitated by this current election cycle. A search for "election anxiety" yields online articles from The Atlantic, US News, Newsweek, Time Magazine and The Washington Post, among other news outlets.

As an Alexander teacher, I spend my days teaching my students how to self-regulate so they can manage moments of spiking anxiety. To be an effective teacher, I use the very tools I am teaching, at work and in my life.

No matter which side of this debate you are on, it is likely that you feel strongly, believe in your own point of view and fear the outcome. It is also likely that your feelings are being heightened by the coverage you are exposed to.

What can you do to take care of yourself? Here are some resources, including simple tools I teach my students.

1. Remind yourself that you don't have to hold your breath.

When we experience fear or other strong emotions, we sometimes freeze. It may be a tight jaw, it may be subtle or not so subtle clenching in shoulder, chest or abdomen. Frequently, tension reduces the mobility of our torso, and breath requires movement in the ribs.

2. Stand with your back touching a wall or door.

Use the contact with your back against the surface to bring you into the present environment. See and name what is around you, in as much detail as you can. (Example from my studio: Area rug with floral patterns, in beige, burgundy, sage green; massage table with a green cotton sheet that has stripes; dark brown wood computer desk with a cordless phone/answering machine and an iMac; fireplace mantle surrounded by teal tiles).

3. Research what actions you can take to assure your vote counts and that your elected officials represent your values.

Search your state and federal nominees to find out where they stand on the issues (search "[your state] 2016 candidate platforms". In addition to finding out where they stand, you can find out how to support the campaign of those who represent your views.

4. Learn how to bring awareness to, change the subject, and minimize participation in conversations that upset you.

It is possible to effectively bring awareness and shift the conversation without shaming anyone. This article from the New York Times is entitled "Lessons in the Delicate Art of Confronting Offensive Speech"

5. If someone has decided who they are voting for, there is no need for discussion. If speaking to an undecided voter, learn how to listen to what matters to that person.

Here is an article "5 Ways To Have Great Conversations"

6. Limit your exposure to media

Once you have done your research and know which candidates represent your values, and how you can take action to improve their chances in the election, take a media vacation. This has not been easy for me, but I have designated media black out days, when I do not read or watch anything about the election.

7. Have an Alexander Lesson

Alexander Technique teaches mindfulness in daily living. Akin to meditation, Alexander Technique teaches conscious inhibition, or how to calm your "flight or fight" response.

This article in Wikipedia explains the neural mechanisms of mindfulness techniques.

This blog was originally posted at brookelieb.com

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Brooke1web.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com[/author_info] [/author]

Being A “Yes" to Life, Without Losing My Reason

by Brooke Lieb

I have been involved in business and life coaching and spiritual communities that were all about being a yes. “Being a Yes” means looking on the positive side of things, going for it, not taking no for an answer, and with that, the dark underside of self recrimination, FOMO (fear of missing out), shame if I’m not being a yes, and the uncomfortable feeling that comes when you say yes in times when a “no” is more authentic.

by Brooke Lieb

I have been involved in business and life coaching and spiritual communities that were all about being a yes. “Being a Yes” means looking on the positive side of things, going for it, not taking no for an answer, and with that, the dark underside of self recrimination, FOMO (fear of missing out), shame if I’m not being a yes, and the uncomfortable feeling that comes when you say yes in times when a “no” is more authentic.

Over the years, I have come to recognize I have a number of patterns and cycles that are starting to feel out of balance. There have been long periods of time, years or more, when I have been in some form of business or life coaching, or trying different systems and strategies to create results in my personal or professional life, focusing on fitness, focusing on diet, shifting from one system to another. I have read hundreds of self-help books, and have been more or less systematic over the years at making steps to move towards having the life I think I want. I have been fortunate, with good health, access to education, employment and enough success to call my passion for the Alexander Technique my profession. I have experienced very few tragedies or economic challenges that caused me any prolonged stress. I don’t know how much of that is the result of my good fortune, good decisions, or my perception or interpretation of events and circumstances. I don’t know how much is because of how the Alexander Technique has given me access to my reason.

Even with all of that, my tendency is to avoid risk, keep my life simple and operate in a small orbit. I have many stories and rationalizations for why I don’t or can’t do certain things, and there are a lot of “no’s” in my moment to moment choices. I don’t mean saying no to a stimulus, I mean habitually saying “no”.

It ends up being an ongoing balancing act. Too many yes’s or too many no’s tend to throw me out of balance. Too many yes’s, and I can end up overcommitted, spread too thin, exhausted, coming up short, pushing too hard and irritable. Too many no’s, and I may start to feel lonely, isolated, and as though I am not taking advantage of what life has to offer.

How does the Alexander Technique help?

I have a process to assess where I am and what I am doing in the short and long term. If I consider "the need to choose" as a stimulus, the rest of Alexander’s process is consistent. Pause, inhibit my habitual response to “choosing”, send my directions, continue to send my directions while considering my choice in this more integrated state, and move forward. In the case of a decision, I may need to reevaluate and reassess as the choice plays out over time.

My choice may yield an unsuccessful outcome, but if I continue to work with Alexander’s process, I can make a new decision, change my strategy, and seek additional information to assist in how I respond to the outcome. There is always a new stimulus, there are always more moments of making decisions.

I am not implying that I, or anyone else, NEEDS the Alexander Technique in order to access what I have described here, and find balance in the moment. I don’t know, however, how it happens without the Alexander Technique in the mix, because for me, the Alexander principles have been part of the equation for my “balancing act" since I was 20. Considering my peers and family members who haven’t had Alexander principles at their disposal, I would bet good money that I can give credit (lots of it!) to Alexander Technique for helping shape my life, and giving me a way to continue to find that delicate balance.

If you are intrigued by this idea, be sure to visit www.acatnyc.org to find out how you can start learning Alexander principles to help you find more balance in life.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Brooke1web.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com[/author_info] [/author]

Thoughts on Doing and Non-Doing

by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening.

by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening.

This topic is of especial interest to me as I have found a wealth of knowledge in the Tao Te Ching: “Wei wu wei,” or “doing without doing,” is a prevalent theme throughout the text, and it offers considerable insight into various implications of The Alexander Technique. As pointed out by Walter Carrington, we cannot lead a life of non-doing, as we would inevitably starve to death. Carrington says that muscular activity in the body is obviously doing; however, to me this is anything but obvious. Would anyone say, “I’m doing my heartbeat?” Another way to define “doing” is as any volitional or potentially volitional muscular response. I say potentially, as the vast majority of muscular responses and coordinations are allocated unconsciously by the brain through the stimulus of a desired outcome.

Doing without doing is a way of accomplishing an end while avoiding an habitual means to obtain it. This might be achieved by changing one's immediate intention, thus delaying the ultimate outcome. For instance, if my goal is to sit in a chair, I can decide merely to sit, which would trigger a complex muscular coordination involving hundreds of muscles contracting and releasing simultaneously and sequentially. My desire to quickly carry out the action of sitting might allow for little new input into achieving the action, so that if the chair is lower than the average chair, I will probably fall into it, expecting to have been sitting sooner. If I wanted to employ a "non-doing" approach, I could first try to have my desire to sit become the outcome of another intention: my knees bending. If I continuously bend my knees, eventually I will make contact with the chair. Such an exercise would begin to reeducate me from my habitual way of sitting, so that when next I go to sit in a "doing" or habitual manner, it might happen more efficiently. It should be said that this improvement will most likely revert quickly to my more habitual behavior shortly thereafter, unless this type of work continues.

It is our goal to accomplish any end by finding a way to allow a spontaneous coordination instead of imposing one; to consider how this action will be achieved instead of predetermining it; to avoid habitual response patterns and allow for spontaneous ones, even if the latter are at first clumsy or less efficient. Once we have established clarity about this goal, the implications for similar or seemingly related philosophies and mystical ideas can be safely considered, and will not be conflated with the principles and workings of the Alexander Technique.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Ezra-Bershatsky-by-Sandro-Lamberti-Photography-23.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]EZRA BERSHATSKY—A graduate of The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, Ezra has two Bachelor degrees of Music from Mannes College The New School for Music, in vocal performance and musical composition. He is currently training to be a teacher of the Alexander Technique. He has been singing and performing since childhood, and early in his training he discovered that he has a passion not only for making music, but for teaching others. Ezra teaches voice in New York City on the upper west side. [/author_info] [/author]

Returning Home

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

For a lot of people, sexual intimacy is an attempt to return to our bodies and feel whole. We spend so much time in our heads, experiencing life not fully in our bodies, not feeling the integration of our system. There is so much fixation on finding a partner and experiencing intimacy as a way to feel connected and validated. Through Alexander Technique we practice feeling whole so that we don’t need to be in our front bodies grasping for more. We can be aware of our back bodies, our head moving forward and up, neck free, torso widening and deepening, knees moving forward and away. All of the parts create a simultaneous awareness of the whole: one at a time and all together.

A lot of the pain I experience in life comes from a feeling of being disconnected and isolated. There’s a quote I love by Lawrence LeShan, “It is the splits within the self that make for the feeling of being cut off from the rest of existence.” I am slowly learning how to experience myself without all the splits -- to gather all my different sides --shawdowed and bright -- and hold them into a unified whole.

This past winter I was severely depressed and felt as if my Self were fragmented into tiny meaningless pieces. I felt alone in my head, and disconnected from myself, loved ones, or any purposeful connection. My mind was full of vicious and self-loathing thoughts, and I tried to escape the abuse by fleeing from my body and myself and towards someone I was romantically interested in. I have learned, again and again though, that true resolution comes from staying -- creating space for the pain, witnessing it, holding it, and integrating it into my whole self. If I try to reach outside of myself to escape pain, that only takes me further from home.

I recently took a course on Visceral Manipulation, taught by Liz Gaggini. We learned that in order to heal a client’s organ, you must have an attitude of nonchalance and only put some of your attention on the person. The rest of your attention will stay in your body, in the room around you, and beyond. In order to heal another, you must stay whole. If you give too much, you offer the person a fragmented presence, an energy that is coming just from the front of the body -- a grasping, an end-gaining.

This is so true for relationships. When connecting with another person, even someone to whom I’m greatly attracted, I can practice not coming forward into the pull of hormones and craving, but remain in my full body. There is much pleasure to feel just here as I am, inside myself. This is a new and exciting practice, to realize that simply walking around and being inside my body can feel good, especially after the last 5 years of chronic pain and health problems. I am learning how to hold pain as part of the experience, not the only thing. I am learning to accept all the parts of myself, and to hold them in an awareness that is deep and fulfilling.

This past winter I liked someone so much that I lost my awareness of my back body. I fell forward. I fell hard.

And the ironic thing is, I was leaning forward in order to feel a connection -- to return home. But home is back and up into my torso, widening and deepening, my head moving forward and up, my gaze softening, my neck being free.

Here I am again, having remembered, but life is a process of forgetting and remembering, of getting lost in the pieces, and then expanding our awareness to perceive more. Alexander Technique is the gentle practice each day to return to our whole.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/helsinki-sun-headshot.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]MARIEL BERGER is a composer, pianist, singer, teacher, writer, and activist living in Brooklyn, NY. She currently writes for Tom Tom Magazine which features women drummers, and her personal essays have been featured on the Body Is Not An Apology website. Mariel curates a monthly concert series promoting women, queer, trans, and gender-non-conforming musicians and artists. She gets her biggest inspiration from her young music students who teach her how to be gentle, patient, joyful, and curious. You can hear her music and read her writing at: marielberger.com[/author_info] [/author]

Recipe for Change

by Patty de Llosa

by Patty de Llosa

Contrast is crucial, bright/dark, sound/silence. We always forget our deep need for quiet as we go thru our day of achieving, solving, hesitating, and wondering if we’ve done all we should. How refreshing a change would be right then, in the middle of the action!

Well, how about it? What if you could stop to listen at any time, over coffee, while brushing your teeth, even at your desk, leaving off focusing on your papers or computer? You could close your eyes and imagine for a moment that there’s another way of functioning. What would you notice? What would you hear? Perhaps your own heart beating and your own soul calling you home.

Unfortunately, without being aware of it, we often allow ourselves to function in an automatic stimulus-reaction mode that leaves no room for conscious awareness. The pressures of life and our habitual patterns rule our choices until it seems nothing new is possible.

However, new findings in neuroscience show that changing how we do what we do is as important for our wellbeing as eating the right food. Studies in neuroplasticity indicate how new impressions stimulate and even feed our neurons. It’s time to celebrate the fact that what we think changes the physical structure of our brain. When we change our minds, we change our brain.

Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz, a practicing neuropsychiatrist affiliated with UCLA, and author of Brainlock, works with people who have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) by teaching them to change their thinking through a specific four-step program. Well, friends, when you look at it you’ll see that his program could apply to all of us if we want to live more consciously!

The first step is to Relabel your thought, feeling, or behavior—to give it another name. For example that’s what I did some years back when I identified the voice I’d assumed was my conscience to be a tyrannical inner judge (See Taming Your Inner Tyrant). As you recognize and separate out what’s really important to you, you can begin to call some of your drives what they really are, compulsions. They aren’t just another habit, but much stronger, and they live on your energy. In other words, they eat you.

The second step would be to Reattribute what you want to change by calling it by its new name, which could be Automaton, Habit, Tyrant, Mealy-Mouthed Complainer, or any juicy expletive that resonates with you and helps wake you up to its presence.

Dr. Schwartz suggests that the third step, where the real work is, would be to Refocus, replacing your thought or behavior with a new action. What’s more, your brain chemistry will create new patterns of behavior if you can stick at it long enough. As Schwartz explains, “The automatic transmission isn’t working, so you manually override it. With positive, desirable alternatives—they can be anything you enjoy and can do consistently each and every time—you are actually repairing the gearbox. The more you do it, the smoother the shifting becomes. Like most other things, the more you practice, the more easy and natural it becomes, because your brain is beginning to function more efficiently, calling up the new pattern without thinking about it.”

The fourth and final step is to Revalue. As you begin to understand that the old patterns never really worked for you and another way of living is possible, even desirable, the intensity of need for that particular behavior diminishes. You become a happier and healthier human being. This methodology, dear friends, is truly exciting! You can work at any moment to change the chemistry of your brain!

Here are a few exercises you might try:

- Begin to notice which of the demands that come at you in your day you jump to respond, and which you hold back from. Maybe you are like me, good at making to-do lists, but more involved in checking items off than in prioritizing them. When I’m overwhelmed with my list, a couple of questions can help me bring balance to my day: What do I need to do right now? What do I want to do right now? They may not be the same.

- Let it ring. The telephone is our ever-present means of communication with the world. But we don’t have to be its slaves though I sometimes question the intensity of my focus on it. OK, maybe my job is to answer it, but I can begin to take charge of the automaton in me who wants to grab it at the first ring. Try this: Let it ring three times as you allow the sound to penetrate (and perhaps irritate) your newly aware body/mind, then pick it up and respond. Another time, wait two rings, or four. Anything to stay alive to where you are in time and space.

- One way of refreshing your outlook is to take a different route. Whether walking to the subway, driving to the office or taking time for a brisk walk, go a different way, forge a new path. Why does it matter? Ask the nearest neuroscientist!

- When you are at home, the same wake-up-and-live methodology applies. Invite yourself to put on the other shoe first for a week, then change back. Use your other hand to pour the coffee or hold the knife or fork.

- Finally, the uber neuro-improvement challenge will be to experiment with writing with your other hand. Becoming ambidextrous is a royal road to refreshing the brain. So is learning a new language. Investigate crossword puzzles, jigsaw puzzles, brain teasers.

This post appeared originally at Patty de Llosa's blog.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/dellosa.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]PATTY DE LLOSA, author of "The Practice of Presence: Five Paths for Daily Life," "Taming Your Inner Tyrant: A path to healing through dialogues with oneself", "Finding Time for Your Self: A Spiritual Survivor’s Workbook," and co-editor of "Walking the Tightrope: The Jung-Nietzsche Seminars as Taught by Marion Woodman" is a Tai Chi and Alexander teacher who lives and practices in New York City. A contributing editor of Parabola magazine, she has studied many spiritual teachings while making her living as a mainstream journalist at Time, Leisure and Fortune, and raising a family. Visit her blog at www.findingtimeforyourself.com

I Have Time

by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

We are bombarded all day long by stimuli that call us to immediate action. But the pause of saying “I have time” summons an alternative mode of the nervous system, inhibiting the temptation to rush forward under the internal command to “do it now!” When you hold back your first impulse to go into movement by creating a critical pause during which your attention is gathered, you become present to the moment you are living.

So why do we feel the need to hurry? It may be an unconscious sense that danger is near, but it’s not a lion in the street — more likely a deadline or an exam or an unpleasant confrontation. In my case it was often the fear that I wouldn’t finish the job soon enough or well enough to please someone in authority. I discovered that I harbored a Stern Judge who kept an eye on me all day long, commenting on everything I did: “This is more important so get it done first,” or “That’s less important, so hurry through it.” Now, any time I find myself worrying that I don’t have enough time to finish something, I remind myself that I’m creating my own stress. Then I can choose to respond rather than react.

Some people prefer to stay in the fight-or-flight mode, honing their “edge” and paying the price for it in physical fatigue and mental strain. I used to do that too. But even in the middle of the myriad demands to perform at your best, telling yourself “I have time” can provide a mini-break to the nervous system. It offers a moment of choice in spite of the fact that you have to finish the job. It reminds you to attend to your body-being as you press forward with your work, inviting you to release the tensions gathered at the back of your head, and let your thoughts latch onto your body movements. You can interrupt whatever you are doing for just a second to stretch out of the position you are in and into the present moment.

You may well ask, “How can I be expected to stay in the present moment when I’m pressured to finish this job?” O.K. When you have to get something done in a hurry and there’s no choice, try any of these five steps I offer up from my own experience.

First, acknowledge how you really feel about the job. Let your reactions appear in your conscious awareness. Accept them, whatever they may be. “That’s how it is at this moment.”

Second, turn to the only remaining place where there’s freedom: within yourself. Notice the thoughts that are athinking in you and turn them toward the job at hand.

Third, focus your attention on the moves your hands are making — feel the tap of each finger on the computer, or sense the strong muscles that press the freshly glued object together, or revel in the warmth of the soapy water you are washing something in.

Fourth, begin to explore other parts of your body, starting with the back of your neck, where stress tightens our muscles into tough guide-ropes that pull the head out of alignment. Let your thought move whenever and wherever the body moves, seeking out the tense corners and inviting them to release.

Fifth, from time to time interrupt whatever you’re doing, no matter how important, to get up if you are sitting, or at least stretch out and away from the position you are in. If you are standing, think of your legs like tree trunks and send down imaginary roots to ground yourself on the earth while your head floats up above your torso.

Since everything’s connected in the mind-body continuum, you might be surprised to what extent you can relieve your stressed-out system with a brief, non-essential walk down the hall, a peek out the window at the larger world, or even give a seriously deep sigh that engages you right down to the toes. Do anything to interrupt the deadening bond that glues all your attention to what you’re writing, reading, cooking, chopping, building. Truly, the body possesses wisdom that thought doesn’t understand. We can practice listening to it and allow ourselves to expand into present reality. “I have time” helps us do just that.

This post appeared originally at Patty de Llosa's blog.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/dellosa.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]PATTY DE LLOSA, author of "The Practice of Presence: Five Paths for Daily Life," "Taming Your Inner Tyrant: A path to healing through dialogues with oneself", "Finding Time for Your Self: A Spiritual Survivor’s Workbook," and co-editor of "Walking the Tightrope: The Jung-Nietzsche Seminars as Taught by Marion Woodman" is a Tai Chi and Alexander teacher who lives and practices in New York City. A contributing editor of Parabola magazine, she has studied many spiritual teachings while making her living as a mainstream journalist at Time, Leisure and Fortune, and raising a family. Visit her blog at www.findingtimeforyourself.com

The Alexander Technique as a Tool for Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Source: http://blog.mymsaa.org/ms-management-of-cognitive-symptoms/

by Rachel Bernsen

In February 2016, Senior Alexander teacher Judy Stern convened a panel discussion entitled Living with MS and How Alexander Technique Can Help: A Students Perspective. The discussion centered around a student named Ron, who shared the numerous ways the Alexander Technique has been effective for coping with symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis (MS). To protect Ron’s privacy I’ll only use his first name.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society defines MS as “an unpredictable, often disabling disease of the central nervous system that disrupts the flow of information within the brain, and between the brain and body.” Ron credits the Alexander Technique with lessening the severity of his symptoms, improving his quality of life and overcoming several professional prognoses that “there is nothing you can do”. With the aid of the Technique he is still ambulatory, walking with only a cane. He also drives, plays golf and is very physically active.

Ron is in his mid-70s and has been living with the disease for many years. He is a resident of the greater New York metropolitan area, is married with grown children and is a retired business executive. He has studied Alexander regularly for the last seven plus years. During the panel he spoke about how learning the Technique has transformed the way he lives with the disease.

Stern gave a demonstration of working with him in walking, inviting the audience to observe visible changes in his movement patterns. One of Ron’s great concerns is his gait. A few years ago his right knee began to lock involuntarily; spasticity or involuntary muscle contraction is a major symptom of MS. This prevented him from being able to transfer his weight fully onto that leg as he walked. The demonstration showed both Ron and Stern attending to his overall coordination, taking into account the working of his whole body in walking including his head, neck and back. They examined how his whole system responded to weight transfer on to the compromised leg. With an awareness of how he was using his whole body he was able to control his knee spasticity in walking enough to execute a smooth and complete weight transfer onto that leg. Ron was able to release his hips, allowing for an easier leg swing and hence greater flexion through that joint. Conscious releasing of his neck and back muscles helped him resolve the compensatory, maladaptive patterns in his upper body that formed as a result of the knee spasticity. He uses a cane to further improve his balance and coordination but doesn’t need to use it for weight bearing.

Ron discussed how Alexander Technique helps him deal with symptoms of fatigue and stress. These are extremely debilitating symptoms for people with MS. In his Alexander sessions he spends some time lying on the table, practicing constructive rest. The focus in AT on learning to release unnecessary tension often provides him a complete release of spasticity during his lesson time on the table. In addition, a lot of attention is given to releasing his ribcage and improving his breathing coordination. All of these components of the work likely lessen his fatigue and stress level. Working with his breathing in AT piqued his interest in mindful meditation, another modality that has brought him some relief from these symptoms.

Ron describes how his lessons have helped him develop a keen kinaesthetic awareness of himself in movement, learning to pause thoughtfully when he becomes aware of maladaptive patterns, gaining more control over his motor coordination. He describes how it maximizes his abilities in other techniques such as yoga and strength training, both of which he does everyday and have been crucial to his health maintenance. He credits AT as helping him become more adaptable to the rigors of these techniques, able to more quickly and efficiently learn new movements, developing crucial new neural pathways.

The discussion took place at The American Center for the Alexander Technique (ACAT) in New York City during their Annual General Meeting 2016. In addition to Judy Stern, four other teachers (Kim Jessor, Rebecca Tuffey, Joan Frost and myself) who’ve worked with Ron joined the conversation after the demonstration to share methodology, insights and observations. Each of us remarked on what we saw as his extraordinary progress.

The event provided an important context for looking at the benefits of AT through a medical framework, offering an anecdotal example of how Alexander Technique has improved the quality of life for a patient dealing with MS and how it may, with further study, become an accepted practice for functional recovery for MS patients.

This post originally appeared on Rachel's blog: rachelbernsenat.com.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Thierryfoto2.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]RACHEL BERNSEN is a choreographer, performer and a nationally certified teacher of the Alexander Technique, M.AmSAT. Bernsen maintains a private Alexander practice in New Haven, CT. She has been guest faculty at Yale University, Wesleyan University, Miami-Dade College Live Arts Lab, Texas Woman’s University, Seattle Pacific University and the Moscow Dance Agency Tsekh. She is currently a visiting assistant professor of dance at Trinity College and is on faculty at Movement Research. Committed to interdisciplinary performance practice, current collaborators include choreographer Melanie Maar, musicians Taylor Ho Bynum and Abraham Gomez-Delgado, visual artist Megan Craig, and legendary composer Anthony Braxton. http://www.rachelbernsenat.com/[/author_info] [/author]

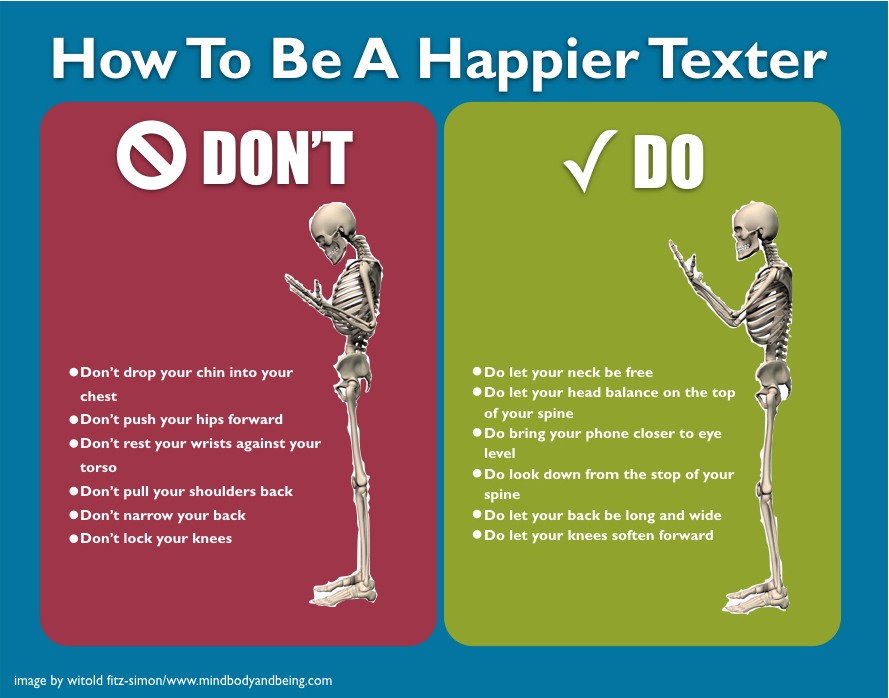

How To Be A Happier Texter

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The Alexander Technique can help you fine-tune the things you do in your life. Instead of your daily routine making you more tired, more compressed, more achy, it can help you find ease, lightness and freedom.

To find out more about how you can save your neck and make your back stronger and freer, come to one of our monthly free introductions to the Technique or to a drop-in group class.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/After-crop1.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]WITOLD FITZ-SIMON has been a student of the Alexander Technique since 2007. He is certified to teach the Technique as a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique’s 1,600-hour, three-year training program. A student of yoga since 1993 and a teacher of yoga since 2000, Witold combines his extensive knowledge of the body and its use into intelligent and practical instruction designed to help his students free themselves of ineffective and damaging habits of body, mind and being. www.mindbodyandbeing.com[/author_info] [/author]

Raising Self-Confidence in Teenagers through the Alexander Technique

by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.

by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.

Being reminded to “sit up straight” was not helping Len. He resisted an upright, healthy posture not only because he didn’t quite know how, but also due to discomfort with his body image.

I am writing about my experience with Len as an example of how the Alexander Technique is uniquely suited for the needs and temperament of young people. Teenagers (and I would include middle school age students in this category) are especially resistant to the agenda of older people and authority figures. For instance, it’s going to be a waste of money if Len thinks he has to change because I or his parents would prefer seeing him in a different shape.

Rather, I try to figure out what Len’s goals are and to frame this process as one that will help his goals, not mine. For instance, I help Len to see how he can feel less stress and pain if he lets go of some of his habitual slumping and tightening. By experimenting within the safe space of the lesson, Len can see how releasing into his full stature actually brings more confidence and energy. He tries adopting this new posture first as if it were a coat he’s trying on. Then, he sees that he actually likes it, not because I told him to but because he experienced it firsthand.

I also encouraged him to bring a basketball to a couple of our lessons and we worked on dribbling and passing using skills of the AT. He happily reported how his playing had noticeably improved with the Alexander influence. Over the course of 10 lessons, Len’s true stature and ease within himself emerged. He learned how, through awareness and conscious choice, he could find an upright, balanced posture that had eluded him for years.

That’s the story of “Len” but I’d like to say, in brief, why the Alexander Technique is well-suited for all young people.

1) In my experience, young people respond quickly (faster than adults) to hands-on and verbal guidance. They are less set in their patterns and more open to change.

2) Given that young people are naturally curious, I find that they can really run with the process of the AT. Rather than having to follow “rules,” students can learn how to manage their own posture and body. This naturally creates confidence and a sense of achievement.

3) Confidence. Though young people are often referred by their parents because of a compromised posture, confidence is usually the second reason. Being a young person nowadays is stressful and they often feel pressure to look a certain way. By slouching, young people might feel they “blend in” and won’t attract undue attention. However, by surrendering their body to tension and slackness, students invariably experience more stress and anxiety because they’ve lost their mind-body connection.

In closing, teenagers are a great candidate for the AT because of the acute pressures they face, their natural curiosity, and their ability to change quickly. I wish it had been sooner than my mid-20s before someone showed me how I could live in my body with more ease and freedom. Young people have such passion and conviction; it’s a wonderful thing to pair that with a little body awareness and wisdom.

This post originally appeared at dancayerfluidmovement.com.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Dan-Head-Shot-13.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]DAN CAYER is a nationally certified teacher of the Alexander Technique. After a serious injury left him unable to work or even carry out household tasks, he began studying the technique. His return to health, as well as his experience with the physical, mental, and emotional aspects of pain, inspired him to help others. He now teaches his innovative approach in Union Square, Carroll Gardens and in Park Slope, Brooklyn. He also teaches adults to swim with greater ease and confidence by applying Alexander principles. You can find his next workshop or schedule a private lesson at www.dancayerfluidmovement.com.[/author_info] [/author]

Standing Up Straight Can Be Just As Bad As Slouching

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

"When I use a word," Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less." (Through the Looking-Glass, Lewis Caroll.)

In my opinion, the Alexander Technique does involve posture, but it defines "good posture" and how to achieve it in a very different way than most approaches.

There's no doubt that bad posture is hard on the body. What most people think of as good posture is generally maintained by using excessive muscle tension in the neck, shoulders and back, which in turn stiffens the limbs as well.

If you habitually slouch in your chair, you probably can notice the amount of extra work that is required to "sit up straight" according to the usual idea. On the other hand, if you habitually maintain what you have been taught to believe is good posture, you may not realize how much you are overworking. You have learned to carry yourself stiffly erect as a child, from relatives or teachers. Or perhaps you learned it as an adult, from a physical therapist, a dance teachers or a yoga instructor. Those who taught you to do this had the best of intentions, but the result can be inflexibility, impairment of full breathing and even pain: ironically, the same problems that can result from slouching.

Several of my students have come for lessons with what most people would say looked like good posture, but who had suffered for years from mysterious neck and back pain that could not be traced to any injury or disease. It was immediately apparent to me, with my Alexander Technique lens, that each of them was holding his back and neck ramrod straight, with very tense muscles. As we worked together on letting go of that tension, these students were able to experience being fully upright with much less effort, and the pain gradually disappeared.

Adapted from "A Lawyer's Guide to the Alexander Technique: Using Your Mind-Body Connection to Handle Stress, Alleviate Pain, and Improve Performance."

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/karen-headshot-67.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]KAREN G. KRUEGER practiced law in New York City for 25 years before training at ACAT, and has now been teaching the Alexander Technique for almost five years. She is the author of the recently published book A Lawyer’s Guide to the Alexander Technique: Using Your Mind-Body Connection to Handle Stress, Alleviate Pain, and Improve Performance (ABA Publishing). Website: http://kgk-llc.com. Buy the book.[/author_info] [/author]

Spreading The Word, Even If The Word Is "Posture"

by Karen Krueger I'm a big believer in speaking up about the Alexander Technique whenever I get the chance. So I jumped right in with a comment when I spotted an article in the New York Times about the importance of posture:

New York Times: Posture Affects Standing, And Not just The Physical Kind

When I checked the comments section again a few days later, there were over a hundred comments -- most of them singing the praises of the Alexander Technique!

Not only that, but I saw no reluctance to identify the Technique with "posture" and no striving to convey all the complexity of the Technique in a few sentences. Rather, each comment mentioned that the Alexander Technique is a great way to improve posture, and added something about the studies that have shown its effectiveness, gave a personal testimonial, or mentioned ways to find a teacher or books to read. Some also responded to other comments in a constructive way. Anyone who reads even a handful of the comments would come away with the clear message that if you are concerned about your posture, you should check out the Alexander Technique.

Because the comments on the New York Times website are moderated, and perhaps also because of the nature of the Times' readership, the comments are often the best part of the articles. The Alexander community's vigorous response to this opportunity to publicize our work will reach thousands of readers who otherwise might never have heard of the Alexander Technique.

So thanks to all of you who added your comments to this story. It only takes a minute or two to add a comment to a news item or a magazine article; I hope we all will make it a practice to mention the Alexander Technique whenever the opportunity arises.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/karen-headshot-67.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]KAREN G. KRUEGER practiced law in New York City for 25 years before training at ACAT, and has now been teaching the Alexander Technique for almost five years. She is the author of the recently published book A Lawyer’s Guide to the Alexander Technique: Using Your Mind-Body Connection to Handle Stress, Alleviate Pain, and Improve Performance (ABA Publishing). Website: http://kgk-llc.com. Buy the book.[/author_info] [/author]

A Better Speaking Voice in One Easy (Alexander) Lesson

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian.

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian.

People who find vocal fry to be unpleasant and irritating often say it makes the speaker sound frivolous. Others reportedly consider it a mark of authority. Some say that young women cannot expect to be taken seriously in the workplace if they speak this way, and others respond that this is anti-feminist.

I do not propose to join this debate over aesthetics, politics and meaning. However, I would like to weigh in on one thread of the argument. Those who defend their own vocal fry and other trendy vocal mannerisms often say that "it's just the way I talk, and I can't change it." Inevitably, speaking coaches, vocal therapists and other such professionals will chime in with "yes you can, if you take lessons in how to speak properly, and by the way, if you don't, you'll damage your voice in the long run."

I'd like to point out another way: the Alexander Technique.

Anyone who talks can make an immediate change in how her voice sounds by changing what Alexander Technique calls her "use." You can try this out for yourself by duplicating an experiment I tried using the recording function on my phone.

Pick a text to read aloud while recording your voice. First, sit comfortably upright and read a few sentences in your normal speaking voice. Then, slump really badly and continue reading without purposely changing your voice. Next, sit up really straight and stiff, and continue for a few more sentences. Finally, relax and resume sitting easily upright, and read a bit more.

When you play back the recording, I think you'll be surprised by how different your voice sounds in the different parts, especially as you assumed postures different from your normal way of sitting. In my experiment, my "good use" voice (sitting like a good Alexander Technique teacher) was resonant and pleasant, though it had the usual weird otherness that I hear in all recordings of myself. My "sitting up straight" voice sounded unpleasantly strident. And I was very interested to hear that when I slumped, I developed a flat-sounding voice with a distinct vocal fry.

Alexander Technique lessons are good for many things: easing chronic pain, increasing efficiency of movement, dealing with stress, and on and on. I'd like to add to that list that the Alexander Technique can turn vocal fry from something you are stuck with to something you can eliminate -- when and if you choose.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/karen-headshot-67.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]KAREN G. KRUEGER practiced law in New York City for 25 years before training at ACAT, and has now been teaching the Alexander Technique for almost five years. She is the author of the recently published book A Lawyer’s Guide to the Alexander Technique: Using Your Mind-Body Connection to Handle Stress, Alleviate Pain, and Improve Performance (ABA Publishing). Website: http://kgk-llc.com. Buy the book.[/author_info] [/author]

Stretching with Ease

by Brooke Lieb

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®.

by Brooke Lieb

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®.

LIEB

Tell us about the inspiration for your book Stretching With Ease.

MINARIK

For a number of years I have been teaching the art of flexibility at a corporate gym facility called Equitable Athletic & Swim Club in mid-town Manhattan. The membership is largely made up of left-brainy people with corporate positions, often high in their chosen professions. Attorneys, doctors, financial wizards, administrative assistants to corporate CEOs—highly articulate people, capable of understanding subtle concepts. They come to class to learn about their bodies; yet fitness is not their field.

I set out to create a worthwhile stretching experience for this fitness audience: teaching them stretching basics while respecting their intelligence. Over the years, I formulated a teaching language that seemed to work. I started explaining as much as I could about why pursuing flexibility might be helpful in their lives, how to allow their bodies to release gently into a stretch, how to align their positions correctly to avoid stressing other body areas, and—a crucial point—exactly where they should be feeling the muscular pull.

Stretching as I teach it emphasizes giving the body adequate time to settle into a position—without rushing into or out of it. Most important is partnering mind with body to increase calmness and minimize fear. Recruit your mind to address your body’s tight spots.

The more I taught, the clearer my instructions became, and my classes began to grow in size. My goal: to clear up the mist of incomprehensibility around flexibility. I wanted to share all the hard-won knowledge I had unearthed over more than two decades of searching. Everyone has his own journey, but I wanted to help people shorten their stretching one.

LIEB

How can stretching contribute to health and well-being, and what are some of the conditions or fitness goals that stretching can help manage or improve?

MINARIK

In some detail, I develop the following benefits of stretching for health, well-being, and fitness improvement in Stretching with Ease:

- Reduces and heals stress

- Prevents injury

- Relieves pain

- Relieves muscular soreness

- Improves posture and body symmetry

- Advances physical and athletic skills

LIEB

You include the Alexander Technique in the “Further Resources” section of your book. When did you first encounter the Alexander Technique, and how has it contributed to your own performing and teaching?

MINARIK

My experience with the Alexander Technique began back in the’70s, when I was beginning to seek better alignment for my body in general, and also physical ease over the many hours I was practicing piano daily for my degree recitals. My study of the Technique long predates my involvement in fitness teaching. Along with other body-work methods, I am sure it was instrumental in making it really easy to start an athletic fitness teaching career in my ‘40s. After taking an introductory group class at a long-forgotten (by me!) studio in the Lincoln Center area, Linda Babits became my first private teacher. A pianist herself, she spent many hours helping me apply the Technique for a pianist’s unique needs. After training with Linda, I also worked extensively with Caren Bayer and Jane Kosminsky.

~

Linda currently teaches group fitness at the New York Health & Racquet Clubs and the Equitable Athletic and Swim Club, both in Manhattan. She pursues classical dance and bodybuilding, and has recently branched out into the study of rhythmic gymnastics, working privately with a former member of the Russian team. Linda is a classically trained pianist, operatic mezzo soprano, and aromatherapist. She lives in New York City. Contact her and/or purchase her book through her website at www.lindasarts.com.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Brooke1web.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com[/author_info] [/author]

How the Alexander Technique Helps My Vision

By Jeffrey Glazer

By Jeffrey Glazer

Just like we have habits of movement and thought, we also have habits of how we use our eyes. My habitual eye pattern is called convergence, which means one or both of the eyes tend to be turned inward. In my case, muscularly my left eye converges to the right, and as a result my peripheral vision to the left is partially cut off. But because my convergence is habitual, I’m usually not even aware of its effect on my peripheral vision until I experience a change. To a behavioral optometrist or other keen observer of the eyes, they can see this pattern in me. However, it’s mostly unnoticeable from the outside, but the experience on the inside when it is changed is significant and clear.

While eye exercises can and do help, there is another approach that I use to help remedy this situation. Using my Alexander Technique skill, I am able to let go of neck and upper back tension, which activates better use of my primary control. The primary control is the relationship between the head, neck, and back; the quality of that relationship, for better or worse, affects movement and overall functioning. Once my neck and upper back is freed up from the habitual tension that I employ, my vision changes in the process!

There are two distinct vision changes that occur.

- First, my vision actually becomes sharper. I am nearsighted (myopia), but I notice that I am a little less nearsighted when free from neck and upper back tension. Even with contact lenses or glasses on, the clarity of my vision improves.

- The second change I notice is that the left side of the world seems to open up for me. This is a result of my left eye convergence dissipating. I experience more peripheral vision on the left side and it feels like I have two eyes again.

What astounds me is that I get these results without directly manipulating my eyes. It comes about as an indirect effect of successfully using the Alexander directions (thoughts sent from the brain to the body) to change the quality of my head, neck, and back relationship (i.e. primary control).

This was one of F.M. Alexander’s main points, that to deal with a specific issue we don’t always have to address it directly. Since everything is interrelated, one can get more bang for their buck by working with the whole. And not only does changing the primary control improve my vision, my movement becomes more fluid, breathing improves, my voice is more resonant, my thinking is clearer, and I feel taller and lighter.

In Aldous Huxley’s 1942 book, The Art of Seeing, he writes the following:

“In myopes especially, posture tends to be extremely bad. This may be directly due in some cases to the shortsight, which encourages stooping and hanging of the head. Conversely, the myopia may be due in part at least to the bad posture. F.M. Alexander records cases in which myopic children regain normal vision after being taught the proper way of carrying the head and neck in relation to the trunk.

In adults the correction of improper posture does not seem to be sufficient of itself to restore normal vision. Improvement in vision will be accelerated by those who want to correct faulty habits of using the organism as a whole; but the simultaneous learning of the specific art of seeing is indispensable.” (Huxley 158).

Huxley was a big proponent of the Alexander Technique as well as the Bates method for improving vision. Alexander himself did not approve of specific exercises without attention to the whole self, so his philosophy may differ from Huxley. However, what they have in common is what I know in myself to be true. The restoration of a balanced head, neck, back relationship, and the consequent correction of posture that comes along with it, results in an improvement in my vision.

Bibliography: Huxley, Aldous. The Art of Seeing. Seattle: Montana Books, 1975. Print.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/jeffrey.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]JEFFREY GLAZER is a certified teacher of the Alexander Technique. He found the Alexander Technique in 2008 after an exhaustive search for relief from chronic pain in his arms and neck. Long hours at the computer had made his pain debilitating, and he was forced to leave his job in finance. The remarkable results he achieved in managing and reducing his pain prompted him to become an instructor in order to help others. He received his teacher certification at the American Center for the Alexander Technique after completing their 3-year, 1600 hour training course in 2013. He also holds a BS in Finance and Marketing from Florida State University. www.nycalexandertechnique.com[/author_info] [/author]

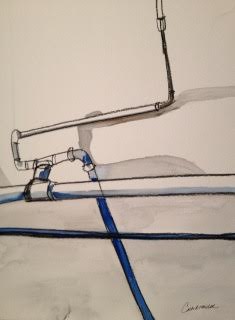

View from the Table, ACAT Pipes

by Cate McNider

by Cate McNider

As an Alexander Technique teacher in training, we are introduced to what is called a ‘lie down’. With the right number of books placed under our heads so that our heads are in right relationship with our backs as if we are standing, and our knees are bent to the ceiling and our feet on the table. This horizontal position put me in visual contact with the external pipes running longitudinally and laterally six or so inches from the ceiling at ACAT. As the teacher directed my thinking to allowing my spine to lengthen and my back to widen, I was seeing these criss crossing symbols above me.

At the beginning of my first term I wished, along with my ‘neck to be free’, to have something more stimulating to look at, but soon I realized the simplicity and beauty of the pipes, the functional details of their construction and the shadows they cast. So in the spirit of awareness, inhibition and direction I created these replicas of various perspectives of the ceiling pipes at ACAT. I decided to photograph them with my iphone and paint them in charcoal and water color, to celebrate my overhead surroundings.

Taking time to have a 5 or 10 minute ‘lie down’, we give ourself the gift of deepening our awareness of ourselves and seeing what ease can follow with that practice. (see Witold Fitz-Simon’s post on how to do Constructive Rest) Next time you do that for yourself, notice the ceiling, see what is above you and if you can let go more into what is underneath you, and you might find when you return to vertical, you most likely are more up than when you went down!

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/McNider.jpeg[/author_image] [author_info]CATE MCNIDER is a third year trainee at ACAT and has been a bodyworker since 1991. She came to NYC as an actor in 1985 from studying at the Drama Studio in London for two years after graduating from Sweet Briar College. She performed Off-Broadway as well as solo dance performances from 1986 -2013. In 2002, she became Body-Mind Centering® practitioner, which brought her closer to understanding movement patterns. She produced two one hour improvisational dance evenings in 2005 about her past-lives, ‘RISK, It’s Really All One Dance’ (excerpt on youtube). In 2010 she published a collection of her poetry: Separation and Return. She began painting in the early 1990‘s as a means of expressing experiential states and concepts where words fell short. Paintings are for sale, contact Cate: www.thelisteningbody.com

Continuing Community at ACAT

by Karen Krueger

In my last blog post, I wrote about why I chose to enroll in the teacher training program at the American Center for the Alexander Technique ("ACAT"), and described the unique strengths of the program. Graduating from that program was a bittersweet moment for me, as it seemed I would lose my connection to the community that I was a part of as a trainee.

by Karen Krueger

In my last blog post, I wrote about why I chose to enroll in the teacher training program at the American Center for the Alexander Technique ("ACAT"), and described the unique strengths of the program. Graduating from that program was a bittersweet moment for me, as it seemed I would lose my connection to the community that I was a part of as a trainee.

Luckily, as I soon discovered, ACAT gives its graduates many ways to remain part of the community. To begin with, there is the opportunity to serve as a volunteer faculty member. This meant that I could continue to participate in the training course at a level appropriate to my experience. Working with trainees was an ideal way to hone my hands-on skills, as ACAT trainees are expert at giving constructive verbal and nonverbal feedback. Participating in a training class also allowed me to observe and experience what the trainers were teaching, and to contribute with questions and observations from my own growing teaching practice.

In addition, I learned that ACAT is not just a training program. It is a not-for-profit membership organization, offering free and paid continuing education programs for teaching members and free and paid programming in the Alexander Technique for associate members and the general public. A majority of ACAT's Board of Directors are ACAT graduates.

ACAT teaching members offer monthly free introductions to the Alexander Technique. Volunteering to present or assist in these "Hands-On Demonstrations" is a great way for recent graduates to get valuable experience working with groups on the Alexander Technique. ACAT also sponsors low-cost drop-in group classes in the Alexander Technique, staffed by teaching members who have been active volunteers at the Hands-On Demonstrations.

In addition to these formal connections, ACAT graduates have their own more spontaneous ways of nurturing the ACAT community. Many of the people I trained with remain friends, have exchanges with each other to work on their skills, and refer students to each other. As I become a more experienced teacher, I find that my most valued form of continuing education is exchanging work with the ACAT people I met during my three years in the training course.

If you love the Alexander Technique, you can be a part of the ACAT community, even if you did not graduate from ACAT, by joining as a teaching member (if you are an AmSAT-certified teacher) or an associate member.

To learn more about the benefits of membership, go here.

To learn more about ACAT's teacher training program, go here.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/karen-headshot-67.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]KAREN G. KRUEGER became a teacher of the Alexander Technique after 25 years of practicing law at two major New York law firms, receiving her teaching certificate from the American Center for the Alexander Technique in December 2010. Her students include lawyers, business executives, IT professionals and others interested in living with greater ease and skill. Find her at her website: http://kgk-llc.com. [/author_info] [/author]

The Alexander Technique: Spiraling Our Lives

by Mariel Berger

When something is organized it flows in the most efficient way possible. I just moved into a new apartment and am discovering the joy of changing my habits to create a super organized home. Every object has a place, and that place is set up in relationship to all other things so the dynamic of the house flows effortlessly. The apartment itself is small, but its efficient arranging lets everything be seen as a whole, and function to its potential. Just as when our muscular system is integrated well, we are conscious of how the parts relate to each other: one at a time and all together.

by Mariel Berger

When something is organized it flows in the most efficient way possible. I just moved into a new apartment and am discovering the joy of changing my habits to create a super organized home. Every object has a place, and that place is set up in relationship to all other things so the dynamic of the house flows effortlessly. The apartment itself is small, but its efficient arranging lets everything be seen as a whole, and function to its potential. Just as when our muscular system is integrated well, we are conscious of how the parts relate to each other: one at a time and all together.

In this modern world, it is easy to forget about the Whole, since our days are governed by the clock. Linear Time is structured in a way that you can’t see what came before or what will be. We are trapped in seconds, minutes, days --lost in the fleetingness of moments---each one vanishing as we step forward into the next. What if we allowed time to soften from its hard line into a spiral that wraps and wraps around itself? What if we were able to experience time in its Entire Presence?

From years of anxious doing, humans have learned and constructed different patterns from the ones found in nature. Patriarchy, Capitalism, Western Culture--all these very narrow systems have detached us from our true and effortless flow. Just as Corporate Agriculture turned farming into rows, despite the fact that nature’s most efficient growing shape is nonlinear, years of industrious work regimented and fixed our muscles into an unnatural shape. Tension and pain are from habits that are not aligned with nature’s organization.

Western Culture worships lines----------------------------------------------------->

[Linear Time] ---------------------> [GRIDS]-------------------------> [Boxes]------------>

Time in one fixed and narrow arrow always pointing from past to future.

[Lists] [Periods]

[Streets] [Fences]

[Wars] [Watches]

[Patriarchy]

All of these linear forces have tried to grid over nature’s beautiful and miraculous organization--the endlessly flowing spirals moving through every part of life. Spirals are found in all parts of nature: galaxies, hurricanes, whirlpools, nautilus shells, cacti, cauliflower, cabbage, sunflowers, pine cones and even inside us. “Examples of spirals in the human body include the spiral waves of blood flow, twisting curves in bones, and the corkscrew-like umbilical cord.” There are also spirals throughout our muscular system. “The human body is fundamentally built upon spiral design and moves most efficiently in accord with spiral motion.” Carol Porter McCullough via Raymond Dart discusses the “double spiral arrangement of the human musculature” here.

In Alexander Technique we are constantly practicing connecting to the spirals within us, as well as allowing our walk to return to its natural spiral motion. The more we practice Alexander Technique, the more we expand our experience from two dimensional to three dimensional. As our relationship to our bodies shift, our thought process becomes three dimensional, and our experience of time softens from a line into a spiral. Instead of end-gaining or moving in a two dimensional straight line from point A to point B, we find the infinite three dimensional spiral which lets us experience the whole and the parts: one at a time and all together. We allow for our neck to be free, head to move forward and up, torso to widen and deepen, knees to move forward and away, simultaneously and part by part. We pay attention to each piece while remembering the connection to the fluid spiral within and around us.

Just as Alexander Technique organizes our bodies, in Permaculture Design, a practice of efficient and sustainable gardening/farming, we are encouraged to organize our gardens to mimic nature’s shapes. Many people arrange their gardens in spiral pyramid designs. “The Herb Spiral is a highly productive and energy efficient, vertical garden design. It allows you to stack plants to maximise space – a practical and attractive solution for urban gardeners...This Permaculture design maximises the natural force of gravity, allowing water to drain freely and seep down through all layers – leaving a drier zone at the top (perfect for hardy herbs) and a moist area at the bottom for water lovers.” – Adrian Buckley (from here).

Alexander Technique and Permaculture Design are both practices to help the body and land return to an integrative system of parts relating to the whole. Spirals are the essence of nature, and through these practices we organize our bodies and landscapes to resonate with their natural flow. Tiny spirals are in our DNA, pour into our blood, twist into our bones, make up our muscle sheets--and as we walk our arms, hips and torso spiral around our spine. We organize our garden into a spiral of sunflowers and even the sunflowers are endlessly repeating spiraling fractals of themselves. The part is the whole, the whole is the part...and on and on…………Read this piece in any order until you see that the meaning is in every word, and the words combined make meaning. Allow yourself to flow in and out of time, spiralling around and around…..

all together one at a time all together one at a time all together one at a time……..

all together one at a time…….. alltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneatatimealltogetheroneata….…… .... …...

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/helsinki-sun-headshot.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]MARIEL BERGER is a composer, pianist, singer, teacher, writer, and activist living in Brooklyn, NY. She currently writes for Tom Tom Magazine which features women drummers, and her personal essays have been featured on the Body Is Not An Apology website. Mariel curates a monthly concert series promoting women, queer, trans, and gender-non-conforming musicians and artists. She gets her biggest inspiration from her young music students who teach her how to be gentle, patient, joyful, and curious. You can hear her music and read her writing at: marielberger.com[/author_info] [/author]

"Physical Therapy May Not Benefit Back Pain," But The Alexander Technique May

By Karen Krueger and Witold Fitz-Simon

Just this week, Nicholas Bakalar of the New York Times reported on a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on back pain and Physical Therapy. The goal was to determine whether or not treatment with Physical Therapy in the form of manipulation and exercises was effective in treating the back pain of recently-diagnosed individuals. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 60, had no lower back pain treatments of any kind in the past six months, and had symptoms for no more than 16 days. All the participants received education about lower back pain, while one group received four Physical Therapy sessions over four weeks. The results in relief of pain for those who received the physical therapy was reported as "modest," but in the long run not distinguishable from the care received by the control group.

By Karen Krueger and Witold Fitz-Simon

Just this week, Nicholas Bakalar of the New York Times reported on a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on back pain and Physical Therapy. The goal was to determine whether or not treatment with Physical Therapy in the form of manipulation and exercises was effective in treating the back pain of recently-diagnosed individuals. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 60, had no lower back pain treatments of any kind in the past six months, and had symptoms for no more than 16 days. All the participants received education about lower back pain, while one group received four Physical Therapy sessions over four weeks. The results in relief of pain for those who received the physical therapy was reported as "modest," but in the long run not distinguishable from the care received by the control group.

Some back pain is caused by poor posture and movement habits. Physical Therapy, yoga, Pilates, and other approaches can help strengthen muscles, add needed flexibility, etc. But too often they do not change a person's habits: when the person gets busy, they go right back to the habits that got them into trouble in the first place. It makes sense to us that people would not show significant improvement after three months.