by Witold Fitz-Simon

Every one of us has a "sixth sense." Unfortunately, it's nothing fancy. It's not telepathy, or the ability to see ghosts, or anything supernatural like that. It is pretty cool, in its own way, even though most of us take it completely for granted most of the time. Our sixth sense is a "feeling" sense made up of information we get from our bodies.

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Every one of us has a "sixth sense." Unfortunately, it's nothing fancy. It's not telepathy, or the ability to see ghosts, or anything supernatural like that. It is pretty cool, in its own way, even though most of us take it completely for granted most of the time. Our sixth sense is a "feeling" sense made up of information we get from our bodies.

Kinesthesia and Proprioception

This feeling sense, called either proprioception or kinesthesia, works a little differently than our other five senses. Each of the traditional five senses, has its own sense organ: sight has the eyes, sound has the ears, etc. The feeling sense is different.

Instead of getting all its information from one source, your brain takes information from organs in different parts of your body and knits it together into one sense. It compiles information from your muscles, joints, tendons and your inner ear to give you an awareness of movement, effort and the position of your joints and limbs. This awareness, your proprioceptive sense, becomes the foundation for the way you sit, stand, walk around or work at the computer. It informs everything you do.

Why it "Feels Right"

Last week on the blog we looked at habits and how hard they are to break. In an nutshell, this is because our brains take complex behaviors and reduce all the different parts that make them up into a single behavioral chunk. This chunk then gets imprinted into our brains with a positive reinforcement mechanism that includes the chemical dopamine. The way we use our bodies, and the proprioceptive memory associated with that use, is part of that chunked behavior. As a result, it feels good or "feels right" to do the habit in a particular way.

Why "Feeling Right" Can Lead You Wrong

Just because a way of doing something has that feeling of "rightness" to it, that doesn't mean it is necessarily your best choice in any given moment. Your proprioceptive or kinesthetic sense often feeds you bad information. The sense receptors in your muscles, tendons and joints register change. If you raise your arm, for example, they tell you that the position of your arm has changed from one place to another. They tell you that the muscular effort expended by the muscles in your shoulder has changed from one amount to another, as well as the rate at which that change took place. After a while, if there is no more change happening, they reset themselves to this new state. They no longer send information to your brain.

This can lead to two problems. If you do the same thing wrong the same way over and over, after a while your proprioceptive sense will no longer register it. Say you tense your neck all the time you are sitting at your computer, your proprioceptive sense will begin to tune it out. This will begin to carry over into other activities. The misuse will get folded in with all your other behavioral patterns and will begin to feel right. You will only be reinforcing the bad habit.

This, then, leads us to the second problem. In order for your sense receptors to pick up any new information, you will have to create change. If you try and "feel out" a part of your body, perhaps to learn more about it or fix it, you will most likely be adding more effort to that place.

Do the Right Thing

So what's the solution to this awkward situation? Change your relationship to your proprioceptive/kinesthetic sense. Rather than getting caught up in the sensations of your body, open your awareness out to include the space around you as well as the information you get about yourself. Rely on that visual and spatial awareness instead. Staying connected to your other senses and the space around you will give your system the message to be a little less compressed, a little less effortful, a little more expansive.

Better still, try taking an Alexander Technique lesson with a certified teacher. They can show you a whole new way to relate to your body that will help you identify and release your bad habits. They will show you how to repattern the way you use yourself to a more efficient and easeful standard.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/After-crop1.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]WITOLD FITZ-SIMON has been a student of the Alexander Technique since 2007. He is certified to teach the Technique as a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique’s 1,600-hour, three year training program. A student of yoga since 1993 and a teacher of yoga since 2000, Witold combines his extensive knowledge of the body and its use into intelligent and practical instruction designed to help his students free themselves of ineffective and damaging habits of body, mind and being. www.mindbodyandbeing.com[/author_info] [/author]

by Witold Fitz-Simon

A recent cover story in

by Witold Fitz-Simon

A recent cover story in

By Karen G. Krueger

About a year ago, I unexpectedly was handed an opportunity to introduce the Alexander Technique to an audience that has no idea what it is, but needs it desperately: lawyers.

By Karen G. Krueger

About a year ago, I unexpectedly was handed an opportunity to introduce the Alexander Technique to an audience that has no idea what it is, but needs it desperately: lawyers. by Dan Cayer

by Dan Cayer

By Karen G. Krueger

By Karen G. Krueger

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Marjory Barlow was F. M. Alexander’s niece, who took lessons from him and trained under him to become an Alexander Technique teacher in 1933. She was the first person outside of F. M.’s Ashely Place Training course to start her own teacher training program. As a teacher she combines a no-nonsense, straightforward approach to the work with light-heartedness and compassion. Here she is in an interview from 1986.

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Marjory Barlow was F. M. Alexander’s niece, who took lessons from him and trained under him to become an Alexander Technique teacher in 1933. She was the first person outside of F. M.’s Ashely Place Training course to start her own teacher training program. As a teacher she combines a no-nonsense, straightforward approach to the work with light-heartedness and compassion. Here she is in an interview from 1986. by Witold Fitz-Simon

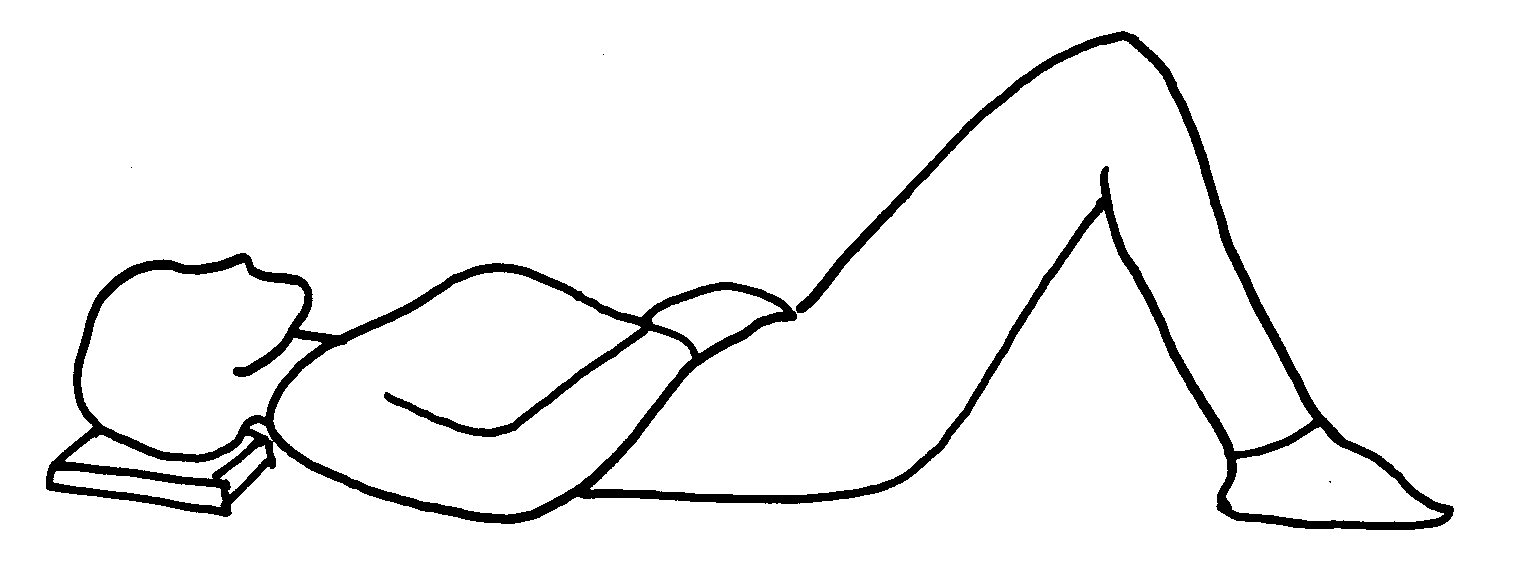

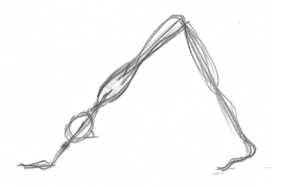

I’ve been noticing over the past few weeks how a few of my Facebook friends have signed up to be part of an event for the month of June: "30 Day Ab Challenge for those who need some motivation like me.” I clicked over to the event page and was surprised that 1.9 MILLION Facebook users have said they are going to take part. I work both as an Alexander Technique teacher and a Yoga teacher, so I spend a certain amount of my working week in gyms. I understand the pressure to look trim and have a slim waist, and I see the effort people put in to the goal of hard abs. I also see the harmful effects this can have on them. Tight abs can be really bad for the body, and here are five reasons why:

by Witold Fitz-Simon

I’ve been noticing over the past few weeks how a few of my Facebook friends have signed up to be part of an event for the month of June: "30 Day Ab Challenge for those who need some motivation like me.” I clicked over to the event page and was surprised that 1.9 MILLION Facebook users have said they are going to take part. I work both as an Alexander Technique teacher and a Yoga teacher, so I spend a certain amount of my working week in gyms. I understand the pressure to look trim and have a slim waist, and I see the effort people put in to the goal of hard abs. I also see the harmful effects this can have on them. Tight abs can be really bad for the body, and here are five reasons why:

by Anastasia Pridlides

I attended the "games teachers play" free member event on April 28th ready for fun. I had been looking forward to this event from the moment it went on the calendar, not only because I really enjoy playing, but also because I love working with groups. I'm always looking for new things to put in my group teaching toolbox. We attendees had a fantastic time as Brooke Lieb, Luke Mess and Mark Josephsburg for shared their teaching games with us. Here are some of the things that I took away from the workshop.

by Anastasia Pridlides

I attended the "games teachers play" free member event on April 28th ready for fun. I had been looking forward to this event from the moment it went on the calendar, not only because I really enjoy playing, but also because I love working with groups. I'm always looking for new things to put in my group teaching toolbox. We attendees had a fantastic time as Brooke Lieb, Luke Mess and Mark Josephsburg for shared their teaching games with us. Here are some of the things that I took away from the workshop.