by Witold Fitz-Simon The Lie Down is an important component of self-care. All it takes is ten minutes once or twice a day. It will give you a chance to calm your mind and rest your body while exploring the principles and the “means-whereby” of the Alexander Technique: observation, inhibition and direction.

Set Up

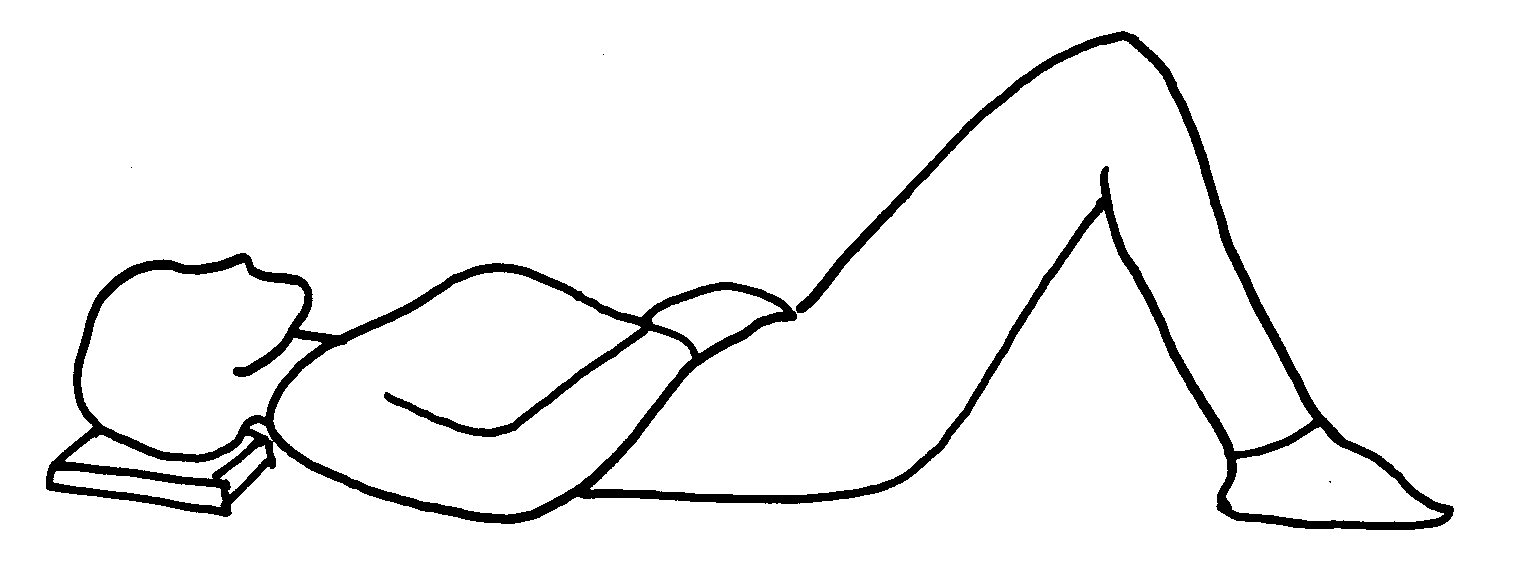

Find a clean, firm, comfortable surface to lie down on. The floor is better than a bed as it will give you a level surface for better support. If your back pressing into the uncovered floor is uncomfortable, lie down on carpet or a folded towel or blanket instead.

Lie back with your head supported by a number of books. There should be enough height under your head so that the back of your neck can be firm but soft to the touch, and that there is a sense of space on all sides of your neck.

Lie with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor.

Lie with your elbows bent and your hands resting comfortably on your torso, perhaps your lower ribs or abdomen.

Expanded Awareness

As you lie here, calm your mind and soften your gaze to become aware of what is going on in the periphery of your vision. Allow the light of the room to come to you, rather than staring out.

Keep the level of your eyes above your cheekbones rather than turning down towards them. This will help to keep you alert.

Expand your awareness to include the room around you and your body. Allow the sensations of your body to rise up to meet you as you look out through your eyes, rather than dropping your awareness down to feel your body.

Inevitably your attention will wander. Gently bring it back to the present moment, looking out at the ceiling with the center of your awareness behind your eyes and above your cheekbones.

Observation

As you rest here, become aware of the touch of your body against the floor. Observe where you might be pressing down into the floor or where you might be holding yourself up away from the floor. Observe where you might be narrowing or compressing. Observe where you might be holding.

Inhibition

As you observe all these places where you might be doing something muscularly in your body, let go of what you do not need. You may find that there are places where something is holding or doing that aren’t ready to let go. Leave those places be.

As you consider your legs, you will find that some muscular effort is necessary to keep them up. See how little you can do without your knees falling in or out. If, as you explore, they do fall in or out, simply send them back up towards the ceiling.

Direction

Without feeling to see if anything is happening, send a message to your neck to be a little freer so that your head can ease away from the top of your spine. Send a message to your back for it to lengthen and widen. Send a message to your knees to ease up towards the ceiling. Send a message to your shoulders and elbows to ease outwards away from your wide chest and back.

Become aware of the movement of your breath. Without trying to shape or change anything, and without losing your expanded awareness, follow each exhalation to its logical conclusion. Allow your inhalations to drop in without actively taking a breath.

Coming Up

When you decide it is time to get up, pause and let go of your first response to the thought. Come back to your expanded awareness. Use the process of coming up as an opportunity to explore your expanded awareness. Once you have got to your feet, pause.

Once again, send a message to your neck that you would like it to be a little freer so that your head can be balanced in poise at the top of your spine rather than being held in place. Send a message to your whole torso that you would like it to be long, wide and deep. Send a message to your legs that you would like your knees to be easy and pointing forward and away from you. Send a message to your shoulders that you would like them to widen off your wide chest and back. Do all of this without feeling to see if anything is happening. Then go on about your day.

WITOLD FITZ-SIMON has been a student of the Alexander Technique since 2007. He is certified to teach the Technique as a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique’s 1,600-hour, three year training program. A student of yoga since 1993 and a teacher of yoga since 2000, Witold combines his extensive knowledge of the body and its use into intelligent and practical instruction designed to help his students free themselves of ineffective and damaging habits of body, mind and being. www.mindbodyandbeing.com[/author_info] [/author]

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The standard wisdom is that it is only the muscles of the human body that contact and create movement, but it turns out that this is not entirely true. About ten years ago, research began to show that fascia contained

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The standard wisdom is that it is only the muscles of the human body that contact and create movement, but it turns out that this is not entirely true. About ten years ago, research began to show that fascia contained  Alexander didn't have a teacher to help him solve his vocal problems. He had no one telling him where to begin or how to approach finding a solution, so he began with simple observation and then experimented on a trial and error basis.

Alexander didn't have a teacher to help him solve his vocal problems. He had no one telling him where to begin or how to approach finding a solution, so he began with simple observation and then experimented on a trial and error basis.