by Tim Tucker

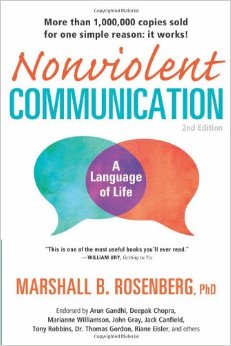

Note: The ACAT Faculty began working with NVC to meet our need for effective and empathic ways of communicating with our teachers-in-training. Alexander's work asks us to address our use on every level. Many of us found NVC supported that desire in the areas of perceiving, listening and speaking in ways that inhibited end-gaining and allowed us to support ourselves and our students in accessing a non-defensive and thoughtful internal state in which to learn how to teach the Alexander Technique. We added the book to our required reading so our teachers-in-training were introduced to NVC while on the course. All of our students are asked to write a response paper to a number of texts, including NVC, as part of their certification requirements. The following is Tim Tucker's response paper. —Brooke Lieb, Director, Teacher Certification Program

by Tim Tucker

Note: The ACAT Faculty began working with NVC to meet our need for effective and empathic ways of communicating with our teachers-in-training. Alexander's work asks us to address our use on every level. Many of us found NVC supported that desire in the areas of perceiving, listening and speaking in ways that inhibited end-gaining and allowed us to support ourselves and our students in accessing a non-defensive and thoughtful internal state in which to learn how to teach the Alexander Technique. We added the book to our required reading so our teachers-in-training were introduced to NVC while on the course. All of our students are asked to write a response paper to a number of texts, including NVC, as part of their certification requirements. The following is Tim Tucker's response paper. —Brooke Lieb, Director, Teacher Certification Program

When I arrived at ACAT and reviewed the list of books we would be reading, I was pleased to note the inclusion of Marshall Rosenberg’s “Nonviolent Communication” among the titles. My Zen teacher had already introduced me to Rosenberg’s work, but my knowledge of NVC remained quite superficial and I was pleased to have an opportunity to deepen my understanding of how it works and what it has to offer.

“Nonviolent Communication” is not a long book (212 pages) but the concepts explored in it seem so novel and the information is so dense in its presentation that it took quite a lot of time and effort to read the book. This is probably because I have labored, like so many other people, under a significant degree of confusion about my perceptions and behavior. I was (and often still am) in the habit of inappropriately melding things that ought to be looked at separately, while simultaneously separating things that need to be considered together. Consider the following basic schemas:

Neutrally observe

↓

Identify Feelings

↓

Identify Needs

↓

Make a request of the other person

The NVC model above, which is grounded in vulnerability, compassion and the ability to offer empathy (as opposed to giving advice or reassurance), stands in striking contrast to the way I, and many others, have typically operated:

Judge

↓

React

↓

Blame/Criticize

↓

Spin in self-validated feelings

↓

Try to change the other person

It’s fairly obvious when two alternative behavioral models are laid out this clearly which one will likely lead to better results. Yet NVC, which appears to be a much more direct route for people to get their needs met, is hardly the norm in our society. Analysis, assessment, criticism, diagnosis, evaluation, interpretation and judgment take the place of neutral observation without our even being aware of it. We don’t even see our own behavior, or that the “pain engendered by damaging cultural conditioning is such an integral part of our lives that we can no longer distinguish its presence.” (p. 165) In this state of near-unconsciousness, hypnotized by our habits and conditioning, it’s very easy to never examine feelings or to reflexively attribute them to other people who in our eyes are inevitably at fault and need to change whenever they fail to act in accord with our values and preferences.

I am very interested in why I and so many other people frequently exhibit the self-defeating patterns of communication delineated by Rosenberg, but the book does not delve much into that fascinating question. What exactly is this “damaging cultural conditioning” alluded to by Rosenberg, and why does it happen in the first place? Early in the text, Rosenberg says “I find that my cultural conditioning leads me to focus attention on places where I am unlikely to get what I want.” (p. 4) In the chapter “Expressing Anger Fully,” he comments on a Swedish prisoner’s confusion of the stimulus triggering his anger (external) with the actual cause of his anger (internal), “By equating stimulus and cause, he had tricked himself…This is an easy habit to acquire in a culture that uses guilt as a means of controlling people. In such cultures, it becomes important to trick people into thinking that we can make others feel a certain way.” (p. 136). As for what Rosenberg thinks causes these unhelpful behaviors, a pretty clear indication is given on p. 23:

Most of us grew up speaking a language that encourages us to label, compare, demand and pronounce judgments rather than to be aware of what we are feeling and needing. I believe life-alienating communication is rooted in views of human nature that have exerted their influence for several centuries. These views stress our innate evil and deficiency, and a need for education to control our inherently undesirable nature. Such education often leaves us questioning whether there is something wrong with whatever feelings and needs we may be experiencing. We learn early to cut ourselves off from what’s going on within ourselves. Life-alienating communication both stems from and supports hierarchical societies, the functioning of which depends upon large numbers of docile, subservient citizens. When we are in contact with our feelings and needs, we humans no longer make good slaves and underlings.”

Thus, Rosenberg thinks that our communication and behavioral problems actually serve the interest of those in power in our society. He is effectively saying that the dysfunction and pain so prevalent among the mass of people and so vividly displayed in their misguided, violent communication sustains the dominance of the elites who control most of the wealth and resources. Simply put, the proletariat is voluntarily colluding with their oppressors in big business and government without even being aware of it, and on an extremely intimate level.

Whether Rosenberg is correct or not in his view on the genesis of life-alienating communication, it clearly is a conditioned behavior; life-alienating communication is the NVC equivalent of F.M. Alexander putting his head back and down and gasping for breath when he wanted to recite Shakespeare. And just as we find in our practice of Alexander, breaking our habit of life-alienating communication in NVC requires us to rein in conditioned, habitual, reflexive behavior by stopping and thinking before engaging in an activity – in this case, before speaking. This stopping, by definition, requires us to slow down and take more time to do whatever we’re doing.

Consider the following passage from “Nonviolent Communication,” which strongly echoes Walter Carrington’s “Thinking Aloud”:

“Probably the most important part of learning how to live the process that we have been discussing is to take our time. We may feel awkward deviating from the habitual behaviors that our conditioning has rendered automatic, but if our intention is to live life in harmony with our values, then we’ll want to take our time.” (p. 146)

Carrington’s version of this way of thinking is:

“I always say to people, ‘Think about time. Realize how much time is a personal thing, how much time is an individual possession….you’re the only person who can give yourself time. Nobody else can give you time. You’ve got to take the time. You’ve got to be prepared to take the time it takes.” Thinking Aloud, pp. 130-131.

NVC and Alexander Technique both provide lenses for people to look at how they unconsciously and habitually harm themselves, and tools for people to learn to stop and apply the “new, correct messages” that can return them to a more natural and healthy way of being and relating. Both AT and NVC require that we slow down and apply a great deal of scrutiny to how we perform a host of deceptively simple activities we formerly took for granted (and often still take for granted). By slowing down and paying careful attention to ourselves and our behavior, we practitioners of these remarkable disciplines are swimming against the tide of our cultural conditioning. Although the tide of cultural conditioning can seem overwhelming it will, through diligent self-work, be overwhelmed. Put another way, if everyone in our society were to suddenly begin to diligently practice these disciplines, the entire machinery of our frenzied, addictive, commercial culture would quite simply collapse.

[author][author_info]TIM TUCKER, a fourth-term teacher trainee at ACAT, was drawn to the Alexander Technique because of its strong affinity with his Zen Buddhist practice. A former stock market analyst and artist, Tim is very interested in studying culturally promoted patterns of addiction, violence and waste in American society.[/author_info] [/author]

by Witold Fitz-Simon

“Invisibilia” is a new radio show/podcast from NPR that combines science and personal stories to explore the unseen forces that shape our behavior. In their episode “The Secret History of Thoughts,” they use the story of an unfortunate young man who is suddenly overwhelmed with violent thoughts as the medium through which to look at the way the mental health profession has evolved its understanding of thoughts and the way they do or do not define us.

by Witold Fitz-Simon

“Invisibilia” is a new radio show/podcast from NPR that combines science and personal stories to explore the unseen forces that shape our behavior. In their episode “The Secret History of Thoughts,” they use the story of an unfortunate young man who is suddenly overwhelmed with violent thoughts as the medium through which to look at the way the mental health profession has evolved its understanding of thoughts and the way they do or do not define us.

by Barbara Curialle

Having spent Thanksgiving week coping with a case of bronchitis, I’ve come away with a few suggestions on dealing with the most irritating (in every sense) part of the problem—the coughing.

by Barbara Curialle

Having spent Thanksgiving week coping with a case of bronchitis, I’ve come away with a few suggestions on dealing with the most irritating (in every sense) part of the problem—the coughing. by Brooke Lieb

When people hear that I teach Alexander Technique, they often comment "Oh, that's about standing up straight", or say something apologetic or sarcastic. Then they inevitably pull themselves up into their version of "Good Posture".

by Brooke Lieb

When people hear that I teach Alexander Technique, they often comment "Oh, that's about standing up straight", or say something apologetic or sarcastic. Then they inevitably pull themselves up into their version of "Good Posture". by Witold Fitz-Simon

The internet has

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The internet has  by Karen Krueger

by Karen Krueger by Tim Tucker

Note: The ACAT Faculty began working with NVC to meet our need for effective and empathic ways of communicating with our teachers-in-training. Alexander's work asks us to address our use on every level. Many of us found NVC supported that desire in the areas of perceiving, listening and speaking in ways that inhibited end-gaining and allowed us to support ourselves and our students in accessing a non-defensive and thoughtful internal state in which to learn how to teach the Alexander Technique. We added the book to our required reading so our teachers-in-training were introduced to NVC while on the course. All of our students are asked to write a response paper to a number of texts, including NVC, as part of their certification requirements. The following is Tim Tucker's response paper. —Brooke Lieb, Director, Teacher Certification Program

by Tim Tucker

Note: The ACAT Faculty began working with NVC to meet our need for effective and empathic ways of communicating with our teachers-in-training. Alexander's work asks us to address our use on every level. Many of us found NVC supported that desire in the areas of perceiving, listening and speaking in ways that inhibited end-gaining and allowed us to support ourselves and our students in accessing a non-defensive and thoughtful internal state in which to learn how to teach the Alexander Technique. We added the book to our required reading so our teachers-in-training were introduced to NVC while on the course. All of our students are asked to write a response paper to a number of texts, including NVC, as part of their certification requirements. The following is Tim Tucker's response paper. —Brooke Lieb, Director, Teacher Certification Program

by Brooke Lieb

[*Please note, I am fully healed and my love of dogs is fully intact!]

by Brooke Lieb

[*Please note, I am fully healed and my love of dogs is fully intact!]

by Karen Krueger

Teaching the Alexander Technique can be lonely. After the structure and camaraderie of training, it can be daunting when we suddenly find ourselves having to create our own schedules, our own ways of self-care, continued learning and practice development.

by Karen Krueger

Teaching the Alexander Technique can be lonely. After the structure and camaraderie of training, it can be daunting when we suddenly find ourselves having to create our own schedules, our own ways of self-care, continued learning and practice development.

by Witold Fitz-Simon

In a

by Witold Fitz-Simon

In a  by Witold Fitz-Simon

On the face of it, Yoga and the Alexander Technique would seem to be two completely different disciplines. Comparing them would be like comparing a dog with an iPad. Although they originated in very different times from very different cultural traditions, and would appear to have emerged out of very different intentions, thematically, they do have a lot in common. In a lecture given in 1985,

by Witold Fitz-Simon

On the face of it, Yoga and the Alexander Technique would seem to be two completely different disciplines. Comparing them would be like comparing a dog with an iPad. Although they originated in very different times from very different cultural traditions, and would appear to have emerged out of very different intentions, thematically, they do have a lot in common. In a lecture given in 1985,  by John Austin

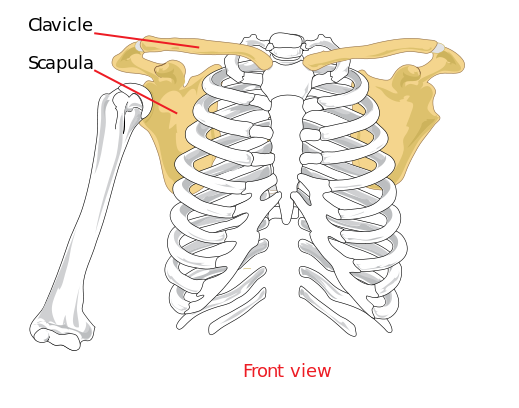

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

by John Austin

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder.

by Judy Stern

by Judy Stern

by Brooke Lieb

This summer, I decided to check some items off my bucket list while I am healthy, happy and had time. I spent Tuesday afternoons in "Acting for the Camera" in the afternoons, and in a Stand Up Comedy class in the evenings. Although I have a Bachelor's Degree in Musical Theater Performance, I haven't worked on a text or studied acting technique in over 25 years. I have never done Stand Up. The first point at which my AT skills kicked in was the act of registering. I tend to think inhibition is about overtly stopping from impulsive and habitual behavior. In this case, inhibition helped me override the habit of keeping in my comfort zone, to do something new, different and unknown.

by Brooke Lieb

This summer, I decided to check some items off my bucket list while I am healthy, happy and had time. I spent Tuesday afternoons in "Acting for the Camera" in the afternoons, and in a Stand Up Comedy class in the evenings. Although I have a Bachelor's Degree in Musical Theater Performance, I haven't worked on a text or studied acting technique in over 25 years. I have never done Stand Up. The first point at which my AT skills kicked in was the act of registering. I tend to think inhibition is about overtly stopping from impulsive and habitual behavior. In this case, inhibition helped me override the habit of keeping in my comfort zone, to do something new, different and unknown.