How the head rests on the top of the spine

In this video blog, Brooke Lieb shows the anatomy of the skull and how it rests on the top of the spine, and includes some details that people can overlook.

Read moreYour Custom Text Here

How the head rests on the top of the spine

In this video blog, Brooke Lieb shows the anatomy of the skull and how it rests on the top of the spine, and includes some details that people can overlook.

Read moreby Cate McNider (originally puplished here)

Scoliosis, the lateral asymmetric deviation of the spine, is idiopathic. That means doctors don’t yet know or fully understand it.

Experientially, we know the causes are as varied as the people that suffer from it. Here’s a synopsis: Muscles pull bones, stimulated by messages sent from the nervous systems motor pathway, to animate the muscle fibers to contract or release. The messaging can also be a suspension of movement, as in holding the diaphragm from inhaling or exhaling. Repetition of such an action or non-action, over time, creates a pathway in the nervous system messaging, which then becomes a habit, which develops into a pattern.

The diaphragm is the nexus of the deviation for the upper and lower side of the spine to be pulled to the right or left in opposition. It’s a powerful trampoline-like muscle that encircles the base of the ribs, creating a boundary from respiratory and digestive systems, massaging both with each action, acting like a pump of sorts. It has anchors, tendons into the spine, the longer of the two on the right side. Over time, that right side anchor has more leverage to pull the upper body into a twist to the right. The lower body, meanwhile, seeks to balance the developing imbalance by pulling back, creating the S-curve. (I’ve found a C-curve to be more common—only one side majorly deviates the spine, usually the upper and again to the right.)

The body’s innate intelligence makes the best of a bad situation, ever attempting to maintain balance, especially to counter strong forces. The mind is the arbiter in shaping the body—how someone accepts a stimulus, or misunderstands a stimulus due to youth and inexperience, begins to shape how they see the world, and in turn shapes or misshapes the body. A force strong enough in an instant, or repeated over time, has the power to imprint itself on a growing spine into pulling it in opposing directions.

And that gets us to the shape of Tao: the light spot in the dark and the dark spot in the light. The spine is the divider of the duality of light and dark; apply a stimulus strong enough to deviate it from an upward balance of the two, and you have expressed a division of mind against itself. Beliefs taken literally by the body have colored the reality of what is true—they warp the frame of the skeleton receiving opposing messages.

There is a naturalness we all are born with, which is colored by our interpretations of our environments, family, culture, language and customs. We are not exactly a blank slate; we bring with us in our spirit knowledge that we will need for this life’s journey, and as we have to learn about where we find ourselves, because we don’t know yet, we make incorrect assumptions, and internalize messages that become the positions from where we act and speak, shaping our minds and thus our bodies. While nature provides all creatures with defensive attributes—the skunk’s pungent scent, the tiger’s sharp claws, the snake’s venom—we humans mostly have our minds to navigate the world and defend ourselves.

We feel before we have language. In our movement, synapses are made between the brain and the body. Our eyes lead us through developmental patterns, homologous, homolateral and contralateral into standing out of curiosity; our world expands and we expand upon our reflexes, into pushing, pulling and reaching. We have all five senses that inform us of our environment, plus the native and primary receptor of vibration, which is feeling. We all felt a situation before we had the language to understand it fully. We felt safe or unsafe. We were hungry or not hungry. We were cold or hot, wet or dry.

In these early years, the feeling groundwork is laid for later complexity. One person may perceive a stimulus as no big deal, but for another person it’s a pivotal event. That pivot, that moment of hinging is in the nexus of the length of the spine or its compression, and the width of the diaphragm or its contraction. This is the center line defining yin and yang, the left side being the feminine and the right being the masculine. Feminine is receptive, masculine is projective. Feminine is space and masculine is form; ergo, there is form in space and space in form. We breathe space (air) into us, drawn in by the diaphragm and pushed out by the diaphragm. Suspend this natural process with a shock and then repeatedly out of fear, and it can become an unconscious habit of withholding the inhale or exhale. Add the effect of the stimuli on the heart and you can have an emotional shutdown; the spine deviates from its support of the heart.

Our strengths and weaknesses are readily perceptible to one who sees and understands the language of the bodymindspirit. Yes, I mean that as one word. We are Tao, the whole circle, but when we swing from yin to yang, pulling ourselves apart by giving the mind power beyond our conscious control, it can become a switchback trail that we must retrace, undoing the misunderstandings, letting the spine untwist itself with every recognition.

For example, I was about 7 or 8 when my father said to me that "thinking is superior to feeling.” Whether he meant it as an order, a threat or a suggestion, it’s how I took it that created my future reality. I was standing at the top of the stairs, up from the front door, on the new white carpet, my hands on the railing, poised to make a decision that energetically would become a base of how I would interact in the family. I made a decision in that moment (I didn’t want to be ‘inferior,’ whatever that meant, since I was already competing with two older brothers) to follow what I thought he meant, which energetically resulted in evacuating my solar plexus, to my brain. Subsequent events further affected me and my body, which having shut down my feeling center could not support me and the forces were greater than my mind could process. The incoming information went out another pathway and was stored in the body’s tissue. Many other defining moments are what I have allowed for decades to unwind, returning my spine to an upward length and width, to wholeness.

If we take the time to understand this relationship of the mind and the body, we can significantly rewrite what will become our future. Understanding the past that has written itself on our body, we can undo the wires that unevenly hold the muscles in opposition. The muscles that are being held by the information messaged by the nervous system can also be messaged to unhold the information.

It’s a choice: Do you want to create yourself after a Picasso or a Modigliani, or do you want to be free to be you? Who is you? (That's not a grammatical error.) Are you in balanced opposition to gravity or are you suffering under the weight of your thoughts about what you think about reality? Remember, you create your body and your reality! Do you want to keep swinging back and forth on the Coney Island ride of suffering, or do you want to undo the lies you accepted so long ago, and discover how you really feel?! Allowing is the new doing.

(These mindbody truths hold whether you have developed scoliosis or not.)

Cate McNider has been working with the bodymind and spirit for 29 years. Through every stage of her healing and working with others through different modalities, she now finds the Alexander Technique, most actively helps others address pain and stress. She is giving online classes during this time of 'social distancing'. President of The Listening Body® has spent three decades in the Healing Arts — spanning Massage Therapy, Reiki, Embodied Anatomy, Yoga, Body-Mind Centering®, Contact Improvisation, Deep Memory Process® and more — and has further sensitized her instrument through the process of Alexander Technique. Her AT training represents the culmination of a lifetime of work and study and a springboard for future creations. Cate is also a painter and published. www.catemcnider.com and www.bodymind.training.

Stimulus Is Everywhere

by Cate McNider (originally published here on September 30, 2020)

“In one social-science experiment, people were told to spend 15 minutes alone in a room with their thoughts. The only possible distraction was an electric shock they could administer to themselves. And 67 percent of men and 25 percent of women shocked themselves, choosing — as Richard Friedman, a psychiatrist, writes in a Times Op-Ed — “negative stimulation over no stimulation.”

That’s provocative, but let’s go a level deeper: What if the stimulus is not obvious?

Read moreClick here to purchase Back Trouble for Kindle.

by Judy Stern and Jessica Santascoy Deborah "Debby" Caplan, author of "Back Trouble: A New Approach to Prevention and Recovery," was a physical therapist and taught the Alexander Technique for over 50 years. She was a founding member of the American Center for the Alexander Technique (ACAT) and a senior faculty member.

Judy Stern, a faculty member of the ACAT Teacher Certification Program and a teacher with almost 30 years experience, was more than impressed by her cousin's recovery from excruciating back pain after taking Alexander lessons with Debby Caplan. At that time, Judy had been a practicing physical therapist for 18 years, and was excited by the possibilities of pain relief that the Alexander Technique offered. Within four years of her cousin's life-changing course of lessons, Judy moved from Gainesville, Florida to New York City to study the Technique herself, and she was mentored by Debby.

SANTASCOY

Why do you give "Back Trouble" to your students when they have a first lesson with you?

STERN

Back Trouble is a basic Alexander text easily read and understood by anyone who wants clear, accurate medical information and is struggling with back issues. I often say at the end of the first lesson that "everything I have taught you today is explained in the first 4 chapters of this book.” I then ask my students to go home a read those chapters.

I believe that learning should be addressed through multiple channels—ie: the visual sense - reading and video, the auditory sense - verbalization, and the kinesthetic sense - touch—to achieve the most effective introduction to the Alexander Technique. I also use the photos in Debby’s book as teaching tools, and let students know that many of the questions people ask about, including the efficacy of the Alexander Technique, are directly answered in the book.

SANTASCOY

What's an essential part or paragraph of the book and why? In other words, what do you think is important for students to remember from this book?

STERN

This is a challenging question!

I believe this book offers the public a basic understanding of the anatomy and physiology of musculoskeletal pain and explains the efficacy of addressing problems with the principles of the AT.

I first saw this book in manuscript form when Debby was writing it, and threatened to “steal” the chapters on back and neck pain for my physical therapy patients, if she didn’t publish it. I am the Judy Trobe (now Stern) who Debby mentions in the acknowledgments, and I was deeply influenced by Debby.

I am partial to Chapter 5 - "Low Back Pain," and Chapter 3 - "Concepts of Good Use." They are both clear, concise explanations of challenging subjects we Alexander teachers are confronted with explaining daily. I also like chapter 9, Emergency Treatment of the Back.

If I had to choose a section to quote from, it would be "Eliminating Tension":

“Learning to do less with the body is one of the most useful aspects of Alexander’s work for back sufferers. Doing less does not mean being less active, but rather, eliminating all the unnecessary muscle tension and harmful postural habits that can cause, and prolong, back pain.

"As you begin learning to eliminate unnecessary muscle tension, you will be able to stop the tension cycle that invariably accompanies back problems. This cycle occurs because pain causes more tension, which in turn causes more pain, and so on. Many of my patients have found that by using the Alexander Technique they are able to stop this painful cycle themselves and thus avoid taking muscle relaxants and painkillers. They also feel more energetic, since they are not using so much of their energy in the form of unnecessary muscle tension.” (Caplan, 14)

SANTASCOY

The Technique is practical, and helps people change everyday habits. How does "Back Trouble" complement AT lessons?

STERN

Debby was a master at teaching people to apply the AT to daily life. This wisdom can be found on pages 75-79, "Applications To Daily Life," and in Chapter 7, "Positions We All Get Into." The illustrations say everything about what working with ease and better use "looks like." The explanations are simple and clear for the general public (no Alexander Technique jargon). Sitting, standing, and walking are the basic activities of life we all address when teaching the Alexander Technique. Debby addresses them all in these parts of her book.

JUDY STERN was a senior faculty member at the American Center for the Alexander Technique (ACAT). She taught the Alexander Technique for over 30 years. She has a post-graduate certificate in Physical Therapy and a Master of Arts in Health Education from the University of Florida/Gainesville. She was a member of the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania School of Physical Therapy early in her career, and worked for 19 years as a traditional physical therapist. Judy has a special interest in the neurophysiology of the Technique. She has retired from private practice.

JESSICA SANTASCOY is an Alexander Technique teacher specializing in the change of inefficient habitual thought and movement patterns to lessen pain, stress, anxiety, and stage fright. She effectively employs a calm and gentle approach, understanding how fear and pain short circuit the body and productivity. Her clients include high level executives, software engineers, designers, and actors. Jessica graduated from the American Center for the Alexander Technique, holds a BA in Psychology, and an MA in Media Studies. She teaches in New York City and San Francisco. Connect with Jessica via email or on Twitter @jessicasuzette.

by Dan Cayer

I started meditating long before I ever heard of the Alexander Technique. Now, my experience as an Alexander teacher has profoundly affected how I sit on the cushion and even how I approach meditation altogether. A week ago, I taught a workshop at the Interdependence Project called Posture, Pain, and Meditation Practice. My experience there inspired me to write about "good posture."

If we look at a meditator like this, from my perspective as an Alexander Technique teacher I can see a few imbalances which are likely making this posture uncomfortable. The low back is arched, the chest is lifted, the neck braced to keep the head from falling back, etc. But mostly what I want to tell this person is, "Don't try so hard to have good posture!"

A Punitive Approach to Posture

What most of us associate with good posture is that oft-uttered admonition from mom, "Sit up straight." For many of us, there is a "snap out of it!" element to this impulse. There we were, daydreaming and slumping, and Whack! We were chastised to sit up straight. There might be a little shame or guilt lurking about in the moment between being reminded to sit up straight and our attempt to do so. As if it were immoral or embarrassed to be in the posture we were in.

What's not clear from the sit up straight recommendation is where you sit up from? What part leads this movement and where do we get support from? Lacking this important information we tend to lift our chest and arch our back to be more upright.

And yet, sitting up straight never feels that comfortable or satisfying. It feels like we are barely hanging on to this upright posture and it's just a matter of time before we are deposited back into our familiar slump. I would argue that part of the reason we fail to find a comfortable, upright posture is due to the very intensity of our pursuit. When we strive to sit up straight, we neglect such essentials as our breathing, a free neck, and relaxed shoulders to name a few. By the way, I found this photo when I googled "correct meditation posture," and there are loads of other photos in a similar breathless effortful hold.

Good Posture Is within Us Already

But don't take my word for it, here is Suzuki Roshi talking in Zen Mind, Beginners Mind:

"People ask what it means to practice zazen with no gaining idea, what kind of effort is necessary for that kind of practice. The answer is: effort to get rid of something extra from our practice. If some extra idea comes, you should try to stop it; you should remain in pure practice."

It's not that we give up our intention to have a healthy posture. Rather, we accept that good posture can be found within us naturally, just as meditators believe that Buddha nature resides within. If we realize that our posture can be uncovered just like the natural qualities of our mind, it transforms the way we approach our bodies. Good posture emerges when there is a lack of interference.

The last word goes to Roshi:

"We do not need to polish something, trying to make some impure thing pure. By purity we just mean things as they are. When something is added, that is impure."

This post was originally published at dancayerfluidmovement.com

DAN CAYER is a nationally certified teacher of the Alexander Technique. After a serious injury left him unable to work or even carry out household tasks, he began studying the technique. His return to health, as well as his experience with the physical, mental, and emotional aspects of pain, inspired him to help others. He now teaches his innovative approach in Union Square, Carroll Gardens and in Park Slope, Brooklyn. He also teaches adults to swim with greater ease and confidence by applying Alexander principles. You can find his next workshop or schedule a private lesson at www.dancayer.co

Machines That Grind Wonder

We have this recurring nightmare in my house where my wife and I are sitting in the kitchen after putting the kids to bed. After 20 minutes of silence upstairs, just as our withered and awkward adult personalities are again beginning to emerge, we hear a crackle from the baby video monitor which means someone is physically handling the microphone in my daughter’s room. We sink into our stools and resign ourselves to the punishment ahead. My 2 ½-year-old has rocked her wheeled crib across the room and is now cupping the baby monitor in her hands like an evil sorceress. Her nose and mouth fill the small video screen in the kitchen as she asks, brightly, “Can I wake up now?

Read moreFrom July 17, 2014: How To Sleep Better

by Jessica Santascoy

Many people ask me if the Alexander Technique (AT) can help with insomnia and getting a better night’s sleep. Yes, AT can help!

My sleep ritual is inspired by AT principles and strategies, and it’s one of the most effective I’ve ever used. This ritual requires very little effort and it can be done before bed, in bed, or if you wake up in the middle of the night. Also, the order of the steps isn’t important - you can do them in any order you like.

Read moreAnxiety Generates an Endless To-Do List. Don’t Listen to It.

Embedded within everyday anxiety is the hope that if we could only complete the remaining tasks on our to-do lists, then we could rest in an aura of accomplishment and contentment. Anxiety creates its own logic: we should maximize all our moments with doing or thinking about doing. I know it’s hard for me to relax when I think about my swollen email inbox. Email has a field day with my adrenal glands.

Read moreA Poor Epitaph: He Tried to Free His Neck

There’s this very important point in the healing process that’s difficult to detect: it’s when the quest to get better becomes a test of one’s self-worth. “Am I the kind of person who can heal themselves, overcome this challenge, or is it true, as I have quietly believed, that I don’t have what it takes?”

Read moreThree Ways to Make Your Work Set-up Healthier

Consider your office set-up and work habits like investing. Each day that you work has an effect on your body and, like our financial situation, ignoring the body doesn’t make it any less real! You can make a few changes that will be a long-term investment in your health (and therefore your ability to be productive and earn that $).

Read moreby Melissa Brown

As we work and socialize remotely these days, we do a lot of sitting at the computer. Many of us have even added “zooming” to our daily routines. As a result, we often feel stiff and sore. Shoulders, necks, upper and lower backs can start to ache.

The Problem

The problem is simple: when we sit at the computer, we usually pull forward into our screens, crane our necks and slump. Then our muscles begin to ache. To try to undue the slump, we attempt to sit in what we think is “good posture” - a military kind of pose, pulling the shoulders back and tightening the abs. Unfortunately, our “good posture” is just a new uncomfortable tightening that we can’t sustain.

The Alexander Technique can help us find a comfortable, balanced state where we are sitting without pulling ourselves around. In the Technique, we are exploring an easy, free use of the body, where the head is poised on a lengthening spine, the torso is lengthening and widening, and the joints are open and spacious, not tight and/or compressed.

The Set-up

Computer

Your screen should be at eye-level so you can sit comfortably without craning your neck. If you have a laptop, you will need to place some books underneath it to raise the screen up. You’ll also need a separate keyboard. I got mine for about $50 at Staples. If you have a monitor, just make sure that you don’t have to constantly look down or up to see the screen.

Legs

You will want to sit with your feet on the floor and your knees lower than your hips so your legs can fall away from your hip joints, giving you more space in those joints. (If your chair is too low and your knees are higher than your hips, the thighbone will fall back into the hip joint and compromise that spaciousness.) This may require using a different chair than the one you usually sit on.

Arms

Whether you are using the keyboard for typing or the mouse for a zoom meeting, have your hands at an easy distance from the keyboard and mouse. You want to be able to reach them without leaning in, craning your neck and/or slumping.

In order to avoid crowding in the joints of your arms, you’ll want your keyboard and mouse to be positioned so your wrist is below your elbow and your elbow is below your shoulder joint when you are typing or clicking. This allows the arm bones to flow out of the joints.

If your desk does not allow for the wrists to be below the elbows, see if you find a higher chair where your feet can still reach the ground.

The Technique

To find the poise and ease that that we want, we need to stop tensing our muscles and tightening our joints and we need to gently coax our bodies into a new and more beneficial organization. Be aware that if we work too hard in an effort to change, we risk creating a new kind of tension. So be easy with yourself.

Though the Alexander Technique is a practice and it takes time to apply its principles, here are just a few ideas that you can try on your own:

First, you want to let yourself find the support of the chair. You can place your hands under your gluts to find the sit bones - which are the knobby bones on either side of the tailbone. Keep the hands there for a few seconds and then gently pull the bones out to either side. This may help you feel more balanced in your seated position. Then, see if you can release any excess tension in your leg muscles. Let your feet soften and allow them to find the support of the floor.

Release any tension that you sense in your neck and jaw muscles. This will help you stop pressing your head down onto your neck and creating downward pressure on the torso. It will also allow your head to gently poise on top of your spine so your whole spine can begin to decompress upward and your back can release into its true length and width.

As you extend your arms to make contact with the keys or the mouse, see if you notice any unnecessary work in muscles of the shoulders and the arms and if so, let it go.

While you sit, you can choose whether or not to use the back of the chair for support. If you do rest back, make sure your feet are still touching the floor and you can reach the keyboard easily. I often place a firm pillow at the back of the chair behind me so I can reach the keyboard easily. You can actually use the support of the back of the chair or the pillow to help you release your back into length and width.

It is also very important to take breaks and stand or walk around the room at regular intervals.

Melissa Brown is an nationally certified teacher of the Alexander Technique and a graduate of American Center for the Alexander Technique (ACAT). In both her group classes and private lessons, Melissa works with students with physical limitations and pain as well as with people who are simply looking for better posture and more ease in movement. She also really enjoys teaching actors and other performing artists.

If you have any questions about the set-up for the computer or how to apply the Alexander principles, please feel free to email Melissa or visit her website .

Melissa teaching a student

Not Going Out? Try going in.

by Cate McNider

When you can’t go out, go in. Instead of getting more and frustrated and angry, look for shelter within. It’s there — you just have to explore. Here are some ideas on how.

Find a space in your home where you can sit comfortably. Turn off your phone. Close the door. Let anyone else around you know you’re ‘going in’ and you would appreciate not being disturbed. (Or you can just say you’re working.)

Now sit.

Read more

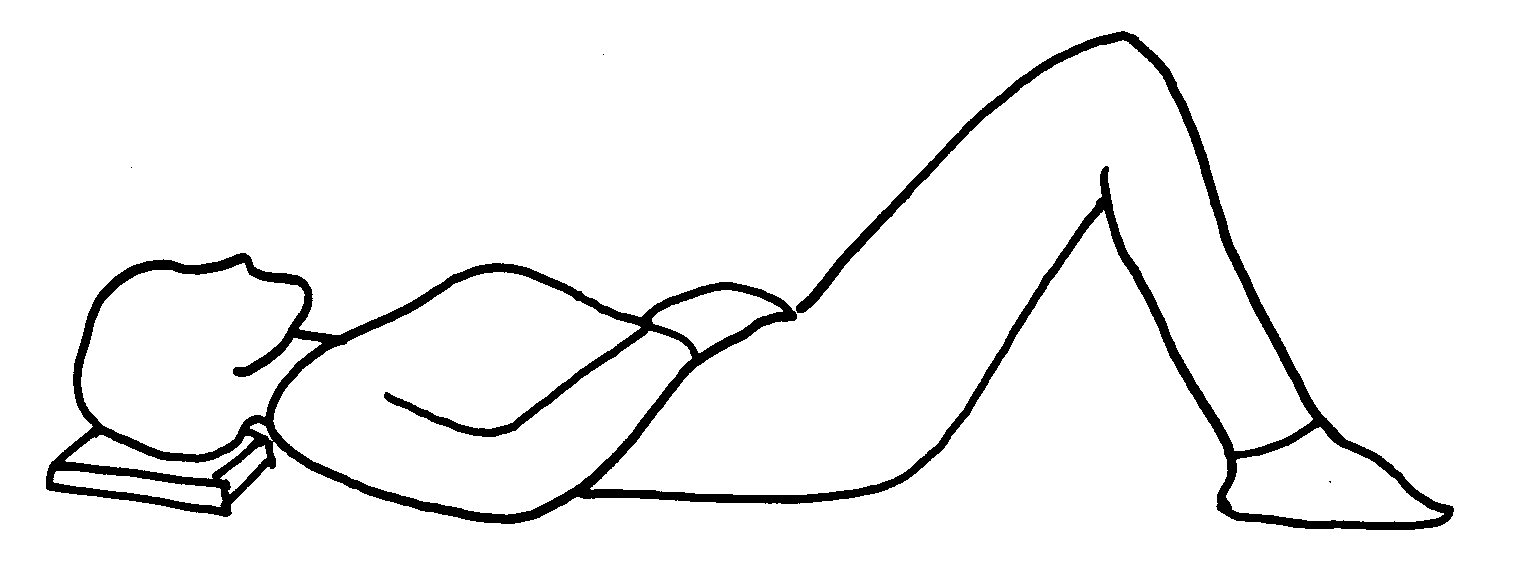

Constructive Rest, Semi Supine, Lie Down

by Witold Fitz-Simon

The Lie Down is an important component of self-care. All it takes is ten minutes once or twice a day. It will give you a chance to calm your mind and rest your body while exploring the principles and the “means-whereby” of the Alexander Technique: observation, inhibition and direction.

Find a clean, firm, comfortable surface to lie down on. The floor is better than a bed as it will give you a level surface for better support. If your back pressing into the uncovered floor is uncomfortable, lie down on carpet or a folded towel or blanket instead.

Lie back with your head supported by a number of books. There should be enough height under your head so that the back of your neck can be firm but soft to the touch, and that there is a sense of space on all sides of your neck.

Lie with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor.

Lie with your elbows bent and your hands resting comfortably on your torso, perhaps your lower ribs or abdomen.

As you lie here, calm your mind and soften your gaze to become aware of what is going on in the periphery of your vision. Allow the light of the room to come to you, rather than staring out.

Keep the level of your eyes above your cheekbones rather than turning down towards them. This will help to keep you alert.

Expand your awareness to include the room around you and your body. Allow the sensations of your body to rise up to meet you as you look out through your eyes, rather than dropping your awareness down to feel your body.

Inevitably your attention will wander. Gently bring it back to the present moment, looking out at the ceiling with the center of your awareness behind your eyes and above your cheekbones.

As you rest here, become aware of the touch of your body against the floor. Observe where you might be pressing down into the floor or where you might be holding yourself up away from the floor. Observe where you might be narrowing or compressing. Observe where you might be holding.

As you observe all these places where you might be doing something muscularly in your body, let go of what you do not need. You may find that there are places where something is holding or doing that aren’t ready to let go. Leave those places be.

As you consider your legs, you will find that some muscular effort is necessary to keep them up. See how little you can do without your knees falling in or out. If, as you explore, they do fall in or out, simply send them back up towards the ceiling.

Without feeling to see if anything is happening, send a message to your neck to be a little freer so that your head can ease away from the top of your spine. Send a message to your back for it to lengthen and widen. Send a message to your knees to ease up towards the ceiling. Send a message to your shoulders and elbows to ease outwards away from your wide chest and back.

Become aware of the movement of your breath. Without trying to shape or change anything, and without losing your expanded awareness, follow each exhalation to its logical conclusion. Allow your inhalations to drop in without actively taking a breath.

When you decide it is time to get up, pause and let go of your first response to the thought. Come back to your expanded awareness. Use the process of coming up as an opportunity to explore your expanded awareness. Once you have got to your feet, pause.

Once again, send a message to your neck that you would like it to be a little freer so that your head can be balanced in poise at the top of your spine rather than being held in place. Send a message to your whole torso that you would like it to be long, wide and deep. Send a message to your legs that you would like your knees to be easy and pointing forward and away from you. Send a message to your shoulders that you would like them to widen off your wide chest and back. Do all of this without feeling to see if anything is happening. Then go on about your day.

WITOLD FITZ-SIMON has been a student of the Alexander Technique since 2007. He is certified to teach the Technique as a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique’s 1,600-hour, three year training program. A student of yoga since 1993 and a teacher of yoga since 2000, Witold combines his extensive knowledge of the body and its use into intelligent and practical instruction designed to help his students free themselves of ineffective and damaging habits of body, mind and being. Visit Witold’s website.

From February 13, 2014: How To Manage Anticipatory Anxiety with the Alexander Technique

by N. Brooke Lieb

When I began my training as a teacher of the Alexander Technique, my biggest "symptom" was not pain, it was anxiety. I had started to have panic attacks, where I felt light headed and would begin to hyperventilate, and I was afraid I was dying. Often, the fearful thoughts centered around having an allergic reaction to something that would prove fatal. (I have had three incidents of strong allergic reactions, one to medication, one to food and one undetermined, none of which has been fatal.)

Read moreGlobal Timeout - Individual Tune-In

by Cate McNider

It has been posited, that this pandemic is the Earth giving us humans time in: ‘Timeout’. Which translates to an opportunity to tune-in to one’s self. The choice has been made for us. How you handle the edict from the Earth, the CDC or WHO, is what you can control. How do you respond? Is it triggering anxiety, worry, desperation and fear? If you are, you have the world’s company — it has indeed gotten real!

relationships can be. The issue is in the tissue.

Read moreOriginally posted June 23, 2014: How to Calm Your Mind and Invite Inspiration to Strike

How many times in your life have you been under the gun to come up with something new and inspiration just isn’t coming? Maybe you have to write a proposal at work, or come up with an idea for a fun outing with the family. Maybe you’ve been hammering away at a problem for an hour and the solution is still beyond your reach. It’s a situation most of us have found ourselves in. Why is it that inspiration can be so elusive in moments of pressure? The answer is something called the startle response. As stress levels rise, our body’s fight or flight response kicks in, creating all sorts of problems that can get in the way of clear and creative thinking:

Tightness in the neck and shoulders

Restricted breathing

A surge in adrenaline

Anxiety

Agitated thoughts

The Alexander Technique can offer you a simple and effective solution to help calm your system down and expand your perspective, giving your subconscious mind a chance to do its work. And it can take as little as five minutes!

Read moreAlexander Basics: Head Forward and Up

by Brooke Lieb

The instruction to allow your head to release “forward and up” is intended to improve the way your head balances on the top of your spine, to allow better distribution of weight through all the weight bearing structures of the body, adjusting for our position (standing, sitting, inclined, in extension, etc..)

Alexander observed that addressing this balance had a global effect on efficiency of muscles, reduced stress on joints, nerves and discs, improved coordination and better stamina for the tasks of posture, balance and movement.

These two videos show movement with the downward force of “back and down”, which is attributed to an over-shortening of voluntary muscles at the base of the skull; and how the same movement can be accomplished with more length in the neck.

Read moreThe Power of a Hug: Why Alexander hands-on work may be good for your health

by Brooke Lieb

I ran into a college classmate the other day, who I had not seen in close to 40 years, although we “see” each other on Facebook. She lives in another state, so it was an extreme coincidence that she was crossing a busy intersection in Manhattan just as I was crossing the other direction. We both went in for a mutual embrace in the middle of the crosswalk, at which point I joined her to double back and walk a bit, so we could catch up. We were not that close during my short time at the same college, and don’t know each other that well, but I know she is a kind-hearted, loving person and the immediate availability, as well as the warmth of her embrace definitely lifted my mood.

Read moreby Brooke Lieb (originally published here)

Many years ago, I was teaching a first lesson to a young woman. Her first statement was “I am an Evangelical Christian.” Her first question was “Does the Alexander Technique promote any religious or spiritual ideology that will conflict with my beliefs?”

I told her no, because the Alexander Technique is not a philosophy or a religion. It fails a key element of cults, in that Alexander Technique promotes the individual learning a process for assessing and revising belief systems through self-exploration. F. M. Alexander implored the teachers he trained to teach and innovate based on their own lived experience, not to copy him.

That being said, many people who study the Alexander Technique are also on a path that includes meditation, mindfulness or some spiritual practice. Sometimes, the Alexander Technique turns out to be the catalyst for getting on such a path.

I am a big fan of the Stephen Mitchell translation of the Tao Te Ching. I recognized in my early 20s that movement and dance were the most effective and direct way for me to reach a meditative state. I don’t study any particular philosophy, and enjoy learning from and experiencing many forms of mindfulness.

A dear friend recently (October 2019) gifted me Michael Singer’s book “The Untethered Soul” which draws on many spiritual and philosophical traditions, particularly Buddhism.

As I read the book, I was reminded of the stories of seekers spending years studying, meditating, going on retreat, all in search of spiritual enlightenment. I got the impression that this enlightenment required decades long practices, was elusive and required sacrifice and deep practice to have a lived experience.

I cannot speak to what is true or possible, but as I was reading Singer’s book, his choice of words and descriptions of non-attachment and enlightenment sounded an awful lot like my lived experiences of non-attachment, achieved through my Alexander Technique practice.

Singer talks about releasing an inner struggle, learning not to identify as my thoughts and feelings, even as I experience them. He writes about choosing happiness, as a point of view, and learning to reduce self-created suffering. At the same time, he acknowledges that we will experience the gamut of human emotion. It is our relationship to it that determines our degree of struggle and resistance in the face of the reality we are in.

This could seem lofty, elusive or grand, but in practice it’s down to earth for me. Since I started lessons 36 years ago, I have used the Alexander Technique to notice how I tighten, stiffen, react and resist life on every level (body/mind/spirit) and how to lessen those tendencies, without waiting for or needing the circumstances to change.

I’ve used my Alexander tools through health scares, the death of loved ones, economic uncertainty, relationship challenges, the common cold, injuries, pain, performance anxiety, panic attacks, celebrations, bouts of anxiety and depression, at parties and on and off throughout most every day.

I expect to continue to react, resist and tighten to life, but I know that living the principles of the Alexander Technique has transformed my experience, sometimes within moments, minutes, hours or mere months, depending on the situation. It doesn’t have to take forever to have a lived experience of non-attachment and to reduce the degree of struggle and suffering.

N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com

Self-Care: It Feels Good and It’s Good For You!

I was working with a client who had originally come to study with me years ago to help her with her singing. She recently returned to lessons, this time to manage a diagnosis of bursitis in her hip joint. No longer working in music, she was now in the world of Not-For-Profits and business. She’d had PT, and was taking Pilates, and something her Pilates instructor said reminded her that Alexander would be a good tool in her toolbox for self-care and healing.

Read more